Antifragility and civil violence

An investment thesis and a concrete idea ($NYT) for a time of novel risks

Disclaimer: This content is for informational purposes only and should not be relied on for investment advice.

A few years ago, I heard an interview Chris Hayes did with former Obama Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, who is also an anti-genocide journalist and activist, and author of the book A Problem From Hell. Hayes asked her a question about genocides broadly that I realized I had also wondered, in the back of my head, for a long time. In cases of genocide, he asked (I’m paraphrasing),

What leads large numbers of previously ordinary people to commit horrific acts of violence?

Powers’ answer was straightforward and has stuck with me: most ordinary people who who engage in violence do so because they come to believe heinous acts of violence have been committed by the other group (typically defined by religion or ethnicity) against their own.1 The initial stories about atrocities committed by the outgroup are usually hyperbole and lies, sometimes concocted by leaders to gain power through violent means. But the stories being untrue doesn’t lessen their power.2

To be clear, I’m in no way suggesting there could be a genocide in the United States. But I was reminded of Powers’ answer when I saw this tweet yesterday:

We already know roughly 70 percent of Trump supporters believe the 2020 election was stolen (it wasn’t), and this poll says 50 percent of Republicans believe “top Democrats are involved in elite sex-trafficking rings.”3 Both of these things are false, obviously, but we have to take this narrative seriously because stories don’t have to be true to inspire civil violence.

Think about it this way: if you knew a group was trafficking large numbers of children and law enforcement wasn’t doing anything to stop it, would you consider violence to protect those children to be morally justified? There may be complexities to consider, but my reaction is of course it would be morally justified, at least up to a point.

Violence isn’t justified in real life because the beliefs about the election being stolen and Democratic elites being part of sex trafficking rings are false. But the question is: what might people who inhabit an epistemic world where these things are true do in response? Given what they believe, they wouldn’t have to be evil to consider violence. This has to be taken seriously, especially in a country with 15-20 million assault weapons and 400 millions of firearms.

There are several potential takeaways from this. I’m going to focus the rest of this post on one familiar to the Destabilized community: we live in a time of unprecedented and poorly understood risks.

In general, financial markets like order, predictability, and confidence, and dislike upheaval, uncertainty, and fear. Between political polarization, climate impacts, and a divisive media ecosystem, we increasingly have more upheaval and less order, which will eventually affect financial markets. As you know, I’ve been thinking about how to invest money in this context and how to protect our savings given these novel risks.

There are well-established ways to bet that a stock or index will decline in value (or hedge against that happening), including shorting and put options.4 But both have two significant downsides:

First, both put options and shorting require you to not only be correct about the decline in value, but also to get the timing right. If the stock stays high until your put option expires, you lose all the money you paid for it, and you’re once again out of position to capitalize on a decline. You’d have to spend more money to buy new puts to reestablish the position. Shorting a stock requires borrowing it in order to sell it now, hoping it will fall so you can buy it back in the future at the lower price and pocket the difference. However, because you have to pay interest on the borrowed shares, your timeline is capped for practical purposes. Again, even if you’re correct that a stock will fall, you also have to be able to predict when it will fall, and that’s incredibly difficult.

Second, both options and shorting carry significant downside risk. Options that expire out of the money – i.e. with the outcome you bet on not having happened – represent money you once had that is now gone. With shorting, borrowing the stock in order to sell it now requires you to pay interest, just as with any other loan of value. Therefore, as you’re waiting for the stock to fall, you’re steadily bleeding money. And, as the saying goes, “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” But the lender of the shares will be happy to accept your interest payments in the meantime.

Buying put options and shorting stocks are highly risky tools for hedging downside risk in an unpredictable market.5 We need a better solution.

To create antifragility in an investment portfolio, we want something that won’t require us to pay interest, will tend to hold its value (unlike an expiring option), and will gain from the upheaval and uncertainty that is likely to increase in the years ahead. We want investments that are solid or better in any conditions and that are likely to gain from turbulence in the years ahead.

One investment that checks these boxes is the New York Times Company (ticker $NYT). [Full disclosure: I own shares in the company.] The New York Times is not only a good company that is likely to grow its earnings and increase its value in the future, it has also already shown itself to be antifragile to upheaval.

[Quick aside: my analysis of the New York Times Company is unrelated to my feelings about the New York Times as a journalistic entity (which are complicated!).]

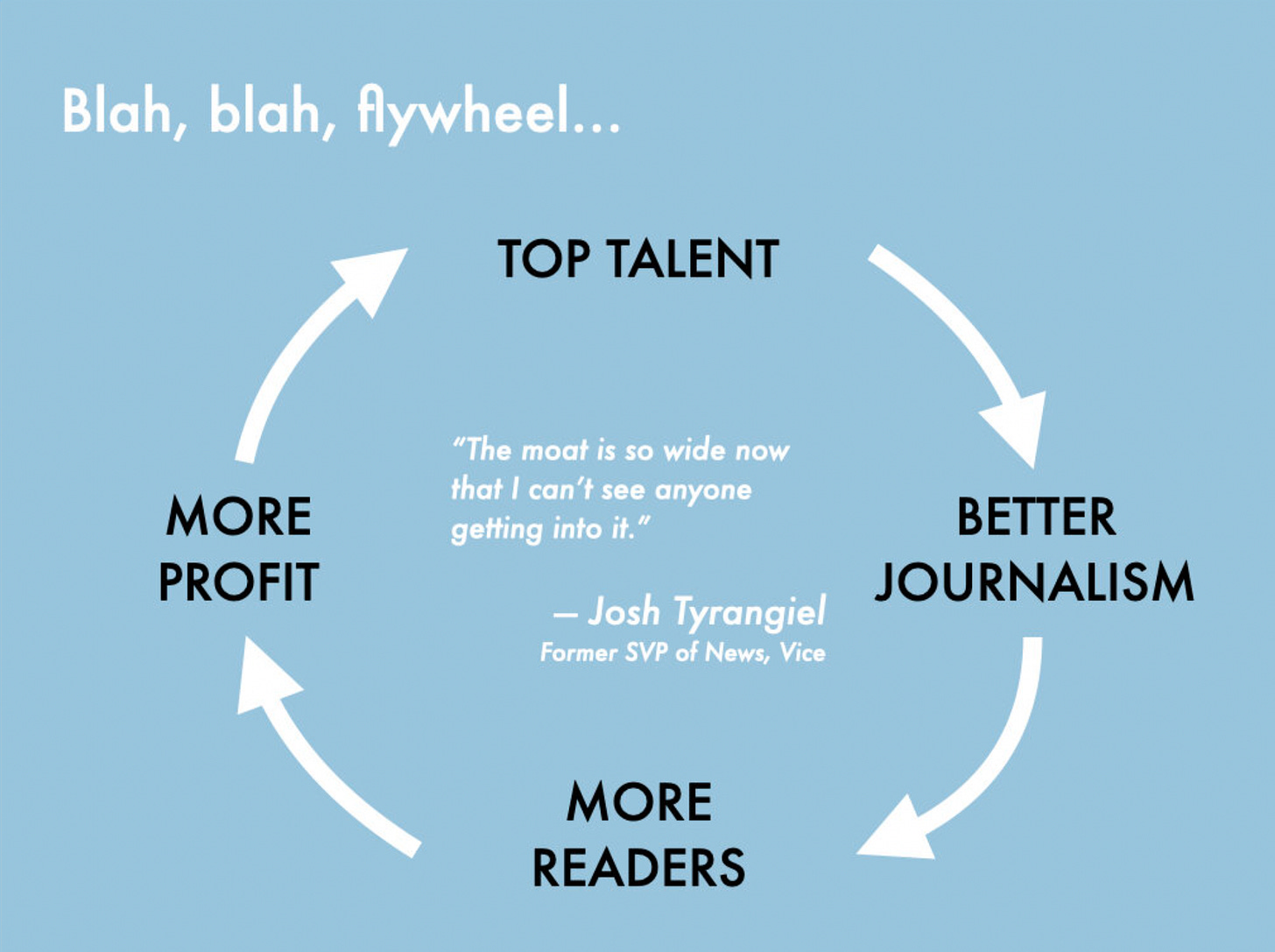

I’ll do a deeper dive in the future, but for now this analysis is a good breakdown of the company. I recommend going through the whole deck. Some highlights:

The analysis goes on to say the company has a large TAM (total addressable market), which it does, especially after its acquisition of The Athletic. The New York Times has become one of and probably the leading English language news source globally. The company is in a strong position to grow revenue and earnings for years to come.

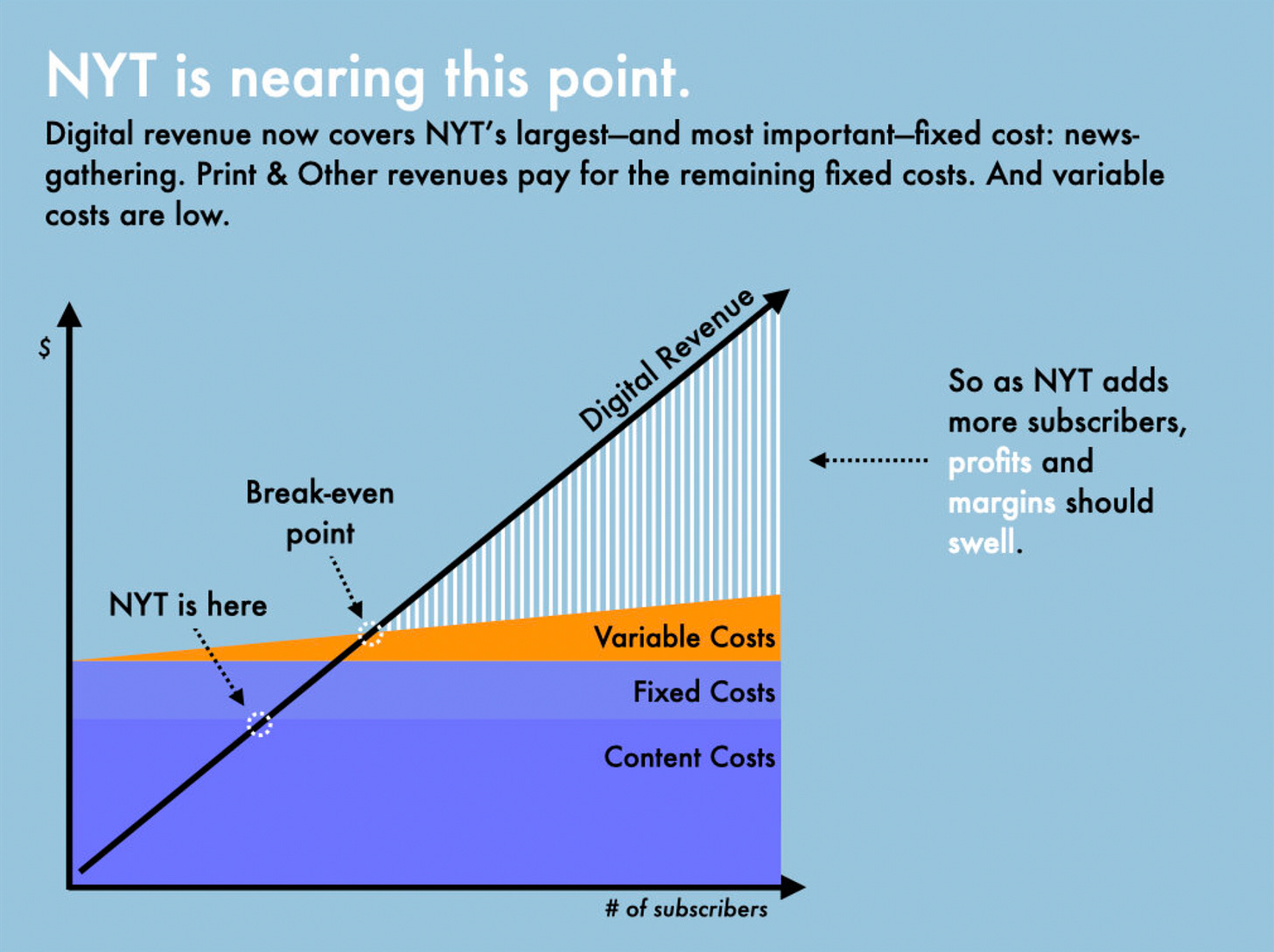

As a predominantly digital media business the New York Times can serve additional subscribers and readers at zero marginal cost, which means beyond a break-even point all new revenue starts to fall to the bottom line. It’s among the most powerful business models ever, and the company is still early in its growth trajectory.

Crucially, the company is undervalued given its current earnings and future growth prospects. I’ll say more about this in the future.

But what makes the New York Times Company an especially attractive investment at this moment in history is its antifragility to turbulence and uncertainty. Check out this chart of quarterly total subscribers:

The key insight here is that the most rapid growth in subscribers (the steepest parts of the upward slope) have happened in the periods of greatest upheaval:

Q4 2016 and Q1 2017, when Trump was elected and then took office, with all the chaos and anxiety that went along with it.

Q1 and Q2 2020, when the pandemic hit, lockdowns happened, and schools closed, with all the strain and uncertainty that came with it.

Q4 2020, when Trump told the Proud Boys to “stand by” in a debate, got Covid, spent days in the hospital, lost the election, lied about it, kept lying about it, and tried to overturn the election. All while Covid was building toward its deadliest peak.

When the world is chaotic, people are anxious and want good information so they can understand what’s happening. This spikes subscriptions to the New York Times (as well as increasing the number of readers seeing its ads). Chaos —> subscribers —> zero-marginal-cost revenue.

This is the kind of antifragile behavior we want the companies we invest in to have going into a period of upheaval.

As with any equity investment, there are risks in investing in the New York Times Company. One unusual one is Sarah Palin’s libel suit against the company. Though it doesn’t have merit under existing constitutional doctrine, it could be a vehicle for right-wingers to try to get the Supreme Court to change the constitutional threshold for libel from “actual malice” to something more like the mistake the Times made about Palin (and later corrected). If this effort succeeds, the Times might have to create a slower, uber-careful, and more expensive fact-checking process. It would also have to spend money and energy defending itself in court against an onslaught of right-wing lawsuits (foundations might offer financial support for legal defense given the frontal attack on a basic guarantor of liberty).

I suspect this ultimately won’t happen – it would devastate Fox News’ business model – but with this Court you never know. The risk should be probabilistically factored in.

It’s not fully self-evident yet, but we’re going to need new, adaptive strategies for investing and protecting savings in this still-new turbulent era. This post offers one place to start.

Most people who do evil things believe themselves to be the hero of the story. Even the Nazis thought they were the good guys.

You could even argue the untruth of these stories can make them more powerful because the atrocities they describe can be as horrific as necessary to inspire retaliatory violence, regardless of truth.

A recent PRRI poll asks the question differently – without reference to partisanship – and finds 25 percent of Republicans agree with the core tenets of the QAnon conspiracy cult. Even if the lower number is true, Trump got 74 million votes in 2020 so 25 percent is still a lot of people (more than 18 million).

I’m focusing here on buying put options as a bet that a stock will fall, ignoring for now the possibility of selling call options, which is the other side of a bet that a security will rise.

In the hedge fund world there are investing strategies built on various tactical mixes of options. I’m general wary of this kind of approach, based both on their complexity and their track record.