Climate change, reverse network effects, and community decay risk

Which climate vulnerable places will get pulled into downward spirals?

On June 23, 2016, a torrential rain storm drenched large swathes of West Virginia. Rainelle, a town of 1,500 in Greenbrier County, was especially hard hit, with 7.5 inches of rain falling in 12 hours. Meadow River, which makes a hard turn just north of Rainelle, spilled over its banks and flooded the town.

As NPR reported in 2021, the water rose so high that Pastor Aaron Trigg had to flee his one-story house and take refuge on his neighbor’s second floor. They were rescued by boat the next day, but every house on their block was destroyed.

What turned the physical disaster into a human calamity was that few Rainelle residents had flood insurance. The community is predominantly low-income and flood insurance, which isn’t included in homeowners’ policies, was unaffordable for most.

"A lot of people in Rainelle were poor, and they didn't have any insurance. They didn't have any way to have any backup plan," [Trigg] says.

With no money for repairs, many people took what they could salvage and left Rainelle for good. "It affected the spirit of the town," Trigg says. Nearly five years later, a lot of homes are gone or only partially repaired. Trigg says all but one of the families on his block left.

After the storm, Rainelle’s population declined by 10 percent.

In 2002, in response to the 9/11 attacks, New York State and City created the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) to help the area recover. The LMDC established grant programs to keep existing residents in the neighborhood, and to attract new ones. There were $6,000 grants for signing a one-year lease, and $12,000 for a two-year lease.

Why did they pay people to live in Manhattan of all places? Dror Poleg explains:

[U]rban economists know that cities become coveted because they are coveted; they become attractive to people because they are full of people. And so, to ensure a city will flourish, it makes economic sense to pay people to kickstart or revive a process by which a critical mass of residents and economic activity attracts even more residents and economic activity.

City and state leaders worried the shock of 9/11 could knock lower Manhattan into the reverse of this dynamic, where an initial cohort leaves out of fear and, as those people leave, the neighborhoods becomes less attractive, causing more people to leave. Lather, rinse, repeat and an area can start to decline. Once this dynamic gets momentum it can be hard to stop, so New York moved quickly to nip it in the bud.

(Plenty of places today pay people to move there.)

New York’s leaders acted aggressively to shore up neighborhoods in lower Manhattan after 9/11 to avoid what began in Rainelle after the flood: a reverse network effect.

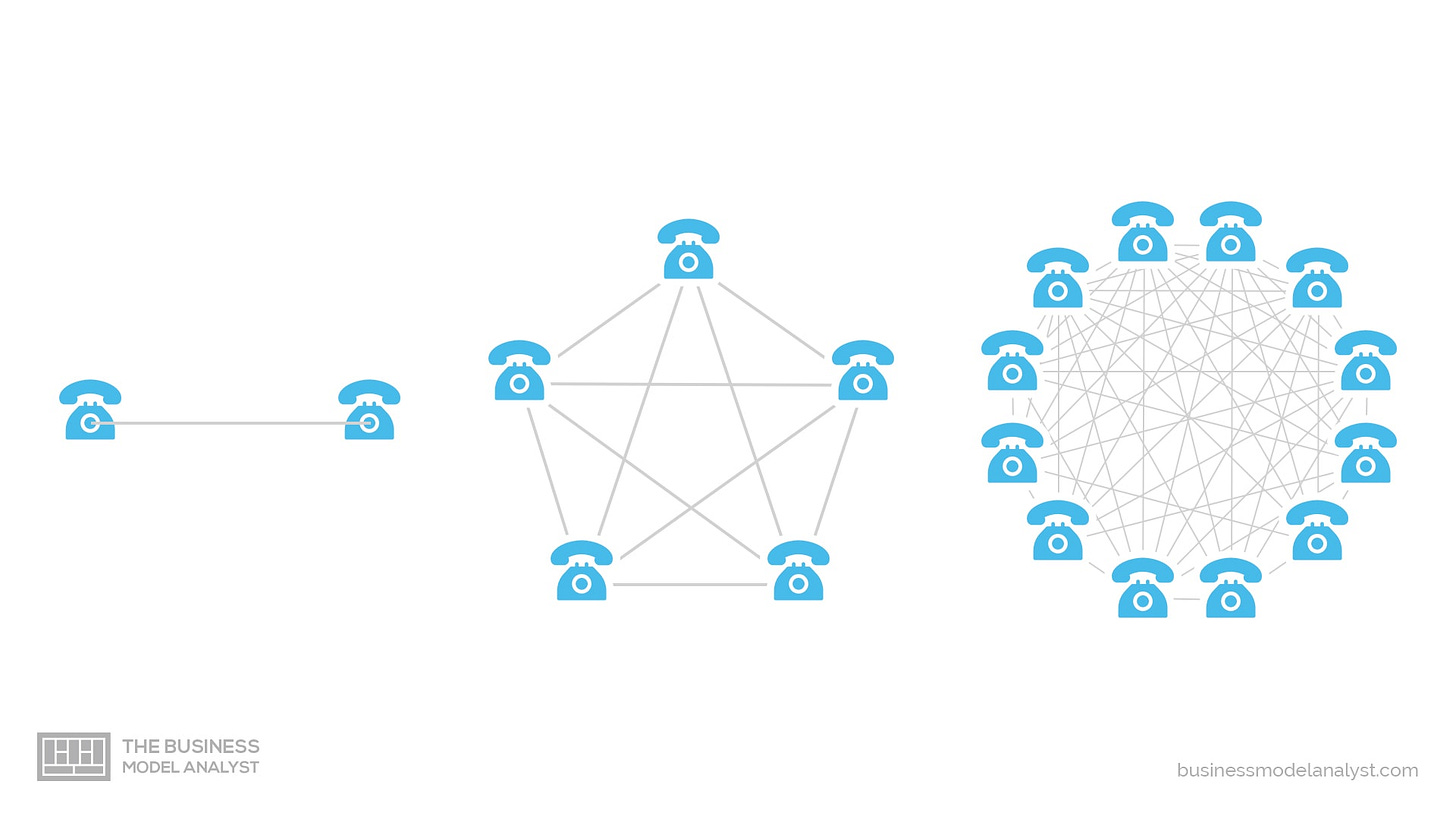

Quick network effects refresher: Network effects are present in any situation where the addition of a new participant increases the value of the system for the existing and future participants. (Or, via Wikipedia, “the phenomenon by which the value or utility a user derives from a good or service depends on the number of users of compatible products.”) Network effects look like this:

Telephones are a great example of network effects. Early in their adoption, when just a few people had them, having a phone wasn’t very valuable – you could only talk to the few other people who had them. As more people got them, having one became more valuable, both to potential new phone owners and to existing ones. The growing value attracted still more people, each of whom increased the value of the network, and so on.

The 2016 flood shoved Rainelle into the early stages of a grinding, heartbreaking reverse network effect. The shock of the flood bruised the town’s spirit and diminished its tax base. Lower revenue reduced its economic capacity to adapt. As a result, few will move there and, gradually, those with the resources will leave. As the population shrinks and the town’s vitality declines, it will become incrementally less appealing to current and potential residents, which will accelerate its decay.

I want to pause here to acknowledge the human catastrophe for the people of Rainelle. It’s painful to watch a community you love suffer. It’s hard to see a future from a decaying place. Property loses most of its value. Mental health is hard to come by, which creates collateral damage – addiction, abuse, etc. It’s a grim reality.

Climate-triggered reverse network effects are a reality, though, and they’re happening in more and more places, not just Rainelle. We need to understand the dynamics, learn to spot them early, and develop approaches to mitigate the human toll.

This leads to the question: How can we assess a place’s vulnerability to reverse network effects triggered by climate shocks? It’s not a precise science, but there are several key risk factors to look for.

Vulnerable to climate disaster – Vulnerable to climate disaster has two elements: a relatively high likelihood of getting slammed by destructive weather events, and a high cost of ruggedization.

Not a locus of economic activity – In places that are centers of economic activity there’s a purely economic rationale for investing in making them climate durable; in other places, there isn’t. Places in the first category, especially metro areas, will be prioritized when adaptation funding is allocated, the other places won’t be.

Low-income, underinsured population – Low incomes means little flood insurance and a general lack of insurance, which transforms weather disasters into into financial and human catastrophes. Low incomes also means a weaker tax base, which constrains a place’s ability to invest in its own ruggedization.

Little political influence – Without political influence, places will be lower priorities when states allocate scarce ruggedization funds. States will focus adaptation resources on rich, connected communities before relatively poor and powerless ones.

Weak sense of civitas1 – A weak sense of civitas means although people may be financially able to tax themselves to raise public money to invest in climate durability, they aren’t willing to do so. Places with lower local taxes will also have less ability to borrow money to invest in ruggedization. In a well-off place with a weaker sense of civitas, some residents will move away rather than swallow higher local taxes, an exodus that may trigger a reverse network effect.

Weak social ties – Places are more durable when they have a higher proportion of longtime residents, strong religious communities, and robust civil society organizations. Places lacking in these things are more likely to see residents leave after a climate shock rather than stay and endure the financial and other costs of adaptation.

There are two takeaways here: a public one related to equity, human dignity, and what it means to be a democratic society; and a private one related risk and decision-making that will have a huge impact on the long-term financial well-being of a wide range of families.

Public – The financial and human risks of climate change-triggered reverse network effects will fall disproportionately on the poor. This is profoundly unjust. There needs to be much more action taken, by both governments and philanthropies, to support people in these communities.

Private – Families need to avoid owning homes/property in areas at higher risk of succumbing to a climate-triggered reverse network effect. For those who already own a home in such a place, they have a decision to make because every such home is exposed to potentially permanent loss of value. Crucially, this is true even for properties not directly vulnerable to flooding, wildfire, etc.

The latter point is so important I want to emphasize it again: If the community a home is in is knocked into a reverse networks effects downward spiral, that property risks losing significant value even if it, itself, in a vacuum, appears relatively safe.

There’s a clear need to be able to evaluate the climate durability/vulnerability of both individual homes and the communities they are part of. I’ve been working on this multi-dimensional problem and have nearly completed a methodology and algorithm for assessing the degree of climate risk of homes and of communities.

It’s one service I provide as part of my Discontinuity Strategies adaptation consulting practice.

Notes:

https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/966428165/a-looming-disaster-new-data-reveal-where-flood-damage-is-an-existential-threat

https://www.drorpoleg.com/ponzi-and-the-city/