Climate migration in America

When will we see large-scale domestic relocation due to climate change?

Today’s climate models have become incredibly sophisticated, but one thing they still can’t predict is exactly when things will happen. It’s true for first order weather-related effects, and even more so for second order effects.

One second order climate impact about which we can’t know the precise timing is large scale human migration. We know people will move away from places that are climate vulnerable to places that are more durable. We expect it will cause social unrest in some of the places migrants go, and lead to gradual declines in the places they leave behind. But we don’t know exactly when it will happen.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately as an unprecedented heat wave has been baking India and Pakistan for weeks. From Vox:

Nearly one in eight people on Earth are enduring a relentless, lethal heat wave that is stretching into its third week.

Triple-digit temperatures are continuing to bake swaths of India and Pakistan, a region home to 1.5 billion people. Extreme heat has also scorched Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in recent weeks… Nighttime temperatures are staying in the 90s, granting little relief for the overheated. And more heat is in store for the coming days.

The heat wave has had critical knock-on effects. Surging electricity demand and stress on the power grid triggered power outages for two-thirds of Indian households. Outages in Pakistan have lasted up to 12 hours, cutting off power when people need cooling the most. Without electricity, many households have lost access to water. The hot weather has also increased dust and ozone levels, leading to spikes in air pollution in major cities across the region.

The connection to potential migration is straightforward. Imagine being a 22-year-old Indian or Pakistani living through this period and thinking about what kind of life you want to have. Does that description sound like a place you want to build a life? Raise a family? If you have the means, how could those conditions not cause you to seriously consider leaving for somewhere else? The case is especially compelling when you consider that things will get worse in the years ahead.

It’s impossible to predict how many of the billion or so people in India and Pakistan enduring this extreme heat will leave, but it will not be zero. If it’s 0.1% of the population, just one out of every thousand people, that would be one million.1 To get a sense of scale, the arrival in Europe of roughly that number of Syrian refugees in 2015 upended the continent’s politics, fueling the rise of authoritarian parties and giving the Brexit campaign a wind at its back.2

Even if relatively few people leave this time, what about next time? That’s the unrelenting nature of the problem highly climate vulnerable places face: there will be a next time, a time after that, and a time after that.

Adaptation can help, though more in some places than others. For example, flooding from climate-intensified rain storms can be usually be managed with approaches like effective drainage systems and reductions in impermeable concrete. But with extreme heat, drought and, in some cases, rising seas, adaptation only gets you so far. Until we cut greenhouse gas emissions to zero, which is a few decades away at best, conditions will grow more extreme and dangerous over time, creating ever more difficult realities for climate vulnerable places and the people who call them home.

Put it all together and it’s hard to escape the conclusion that there will be large climate migrations in the near future.

Migrants often arrive from other countries, but they can also come from a different region of the same country. You might think national brotherhood would ease the social tensions large-scale migration can provoke, but history is full of examples where that wasn’t the case. The receptions given to migrants fleeing the Dust Bowl is one. From ProPublica:

From 1929 to 1934, crop yields across Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri plunged by 60%, leaving farmers destitute and exposing the now-barren topsoil to dry winds and soaring temperatures. The resulting dust storms, some of them taller than skyscrapers, buried homes whole and blew as far east as Washington. The disaster propelled an exodus of some 2.5 million people, mostly to the West, where newcomers — “Okies” not just from Oklahoma but also Texas, Arkansas and Missouri — unsettled communities and competed for jobs. Colorado tried to seal its border from the climate refugees; in California, they were funneled into squalid shanty towns.

The Dust Bowl migration left deep marks on the places people went and the places they fled. From a 2013-14 exhibit at the State of California Capitol Museum:

By 1938, the population in most valley towns increased by 50%. The constant arrival of poor migrants overwhelmed schools and services in the small farm towns located throughout the valley. Throughout the valley, these newcomers competed with residents for jobs. They worked for less money and crossed picket lines. Kern County suffered the worst. Its population increased by 64%, or 52,000 new residents over the decade. Police, medical, housing, and welfare services were stretched to the limit. Townspeople labeled Dust Bowl migrants as “Okies,” no matter where they were from. To them, Okies were ignorant, uneducated, dishonest, and strange. Some wanted to help the Okies by providing food and clothing. Others wanted them to leave California and go back home. Both sides agreed that the newcomers were not prepared for life in California.

The Dust Bowl wasn’t the largest migration in 20th century America. That was the Second Great Migration,3 the exodus of five million Black Americans from the south between 1940 and 1970. Motivated by a desire to escape the oppressive, economically precarious reality of the segregated south, Black families headed north and west in search of better opportunities and a better life.

This mass move to cities in the northeast, midwest, and west was the most impactful internal migration in American history, transforming the country in deep and lasting ways. It influenced the trajectory of the labor movement, the evolution of American music, and the rise of Ronald Reagan and the conservative movement. It created, in many ways, the social realities that defined American politics from the 1960s until today.

Large migrations can drive vast and unpredictable changes in societies.

Extreme weather, sea level rise, drought, and wildfires will, at some point, drive significant internal migration in the U.S. Some in climate vulnerable places will stay and brave whatever comes. Many others will, however reluctantly, leave their homes in search of more durable communities where they can build collective resilience to ever-shifting climate realities.

The reason every Saturday Edition of Destabilized includes the Extreme Weather Watch section is there are almost always climate change-intensified weather events wreaking havoc somewhere, but in today’s fragmented media ecosystem they’re easy to miss. These events are significant, both because they are multi-layered human tragedies, and because they offer clues about what places may begin to see increased out-migration in the future.

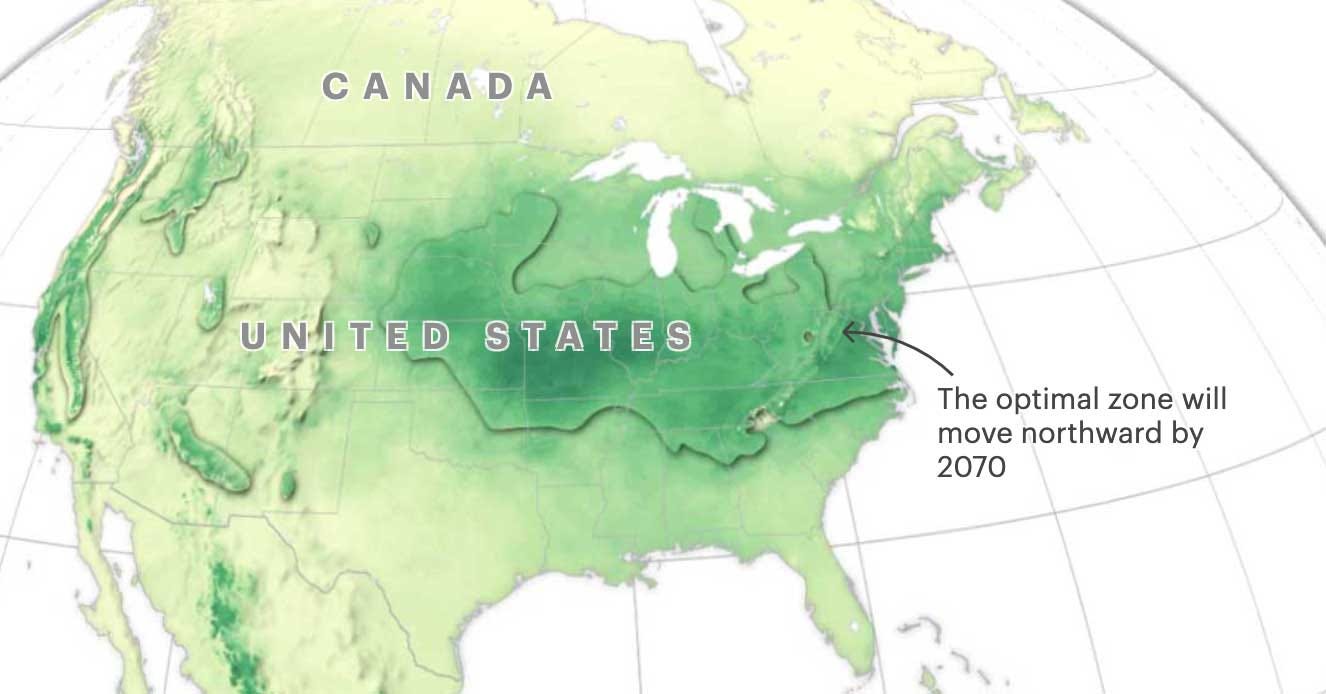

What areas will people eventually leave? To where will they move? These questions are important to consider in making what I consider the most important decision every family will make in the climate change era: where to live.

Climate impacts and migrations will affect the qualify of life of every place in the country. Some communities will be affected relatively little, some considerably diminished, and some so shattered they’ll eventually be all but abandoned.4 Another set of communities will actually be elevated, as the process of ruggedizing against climate change creates a sense of collective purpose, something our country has lacked for long time.

Notes

https://projects.propublica.org/climate-migration/

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/23/magazine/climate-migration.html

https://www.vox.com/23057267/india-pakistan-heat-wave-climate-change-coal-south-asia

https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/exhibits/the-dust-bowl-california-and-the-politics-of-hard-times/

If it sometimes feels not very good to read speculation about how millions of people may respond to a tragic existential crisis they did little to cause, please know writing it often brings up those feelings for me, too.

As I discussed in Climate impacts ripple out.

There seems to be some disagreement about whether the “Great Migration” encompasses the whole period from 1916 to 1970, or whether it describes just the first part, between 1916 and 1940. Those who use it to mean the latter call the second part, the migration of five million Black Americans out of the South between 1940 and 1970, the “Second Great Migration,” which is the term I use here.

Alex Steffen calls this “the ruins of the unsustainable.”