Destabilized Saturday Edition #46

The internet will change everything, Pavlov and his bell, water fears in the southwest, what would you think if you saw it in another country?

I’ve been trying to get a handle on the currents of this moment since the election and have found it challenging. This is partly because the timescales on which societal change happens, even when it’s relatively rapid, are (mercifully) slow compared with human timescales, and right now is a strangely placid moment. But as I’ve continued thinking about the optimistic and pessimistic cases for the future of American democracy, one factor I keep returning to is the internet.

The internet is ubiquitous and so extensively discussed it feels played out. “You know, I really think the internet is a huge deal” is about the least interesting take imaginable. But interesting and consequential are often very different. In 100 years, what will historians see as the key changes, trends, and developments of our age? My money is on the internet and climate change and its impacts.

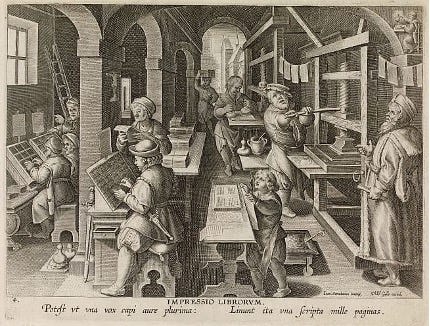

Both things are so large they’re hard to comprehend all at once. Notably, the same was true of the printing press, which was another advance in communication technology that had a massive impact on human civilization. That impact took literally centuries to unfold. I wrote about it more than a year ago and it’s a perspective that, at the risk of immodesty, will remain relevant for a long time:

Here’s the guts of the post:

As we will see, the printing press had an utterly transformative effect on the world. It was arguably the crucial, and at least an essential, ingredient in bringing about no less than the Protestant Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, and the modern nation-state.

Notably, none of these consequences of the printing press were anticipated. They resulted from second and third order effects that seem, at first glance, completely unrelated to the technology itself. The capability to print multiple identical copies of a text isn’t obviously connected to Papal authority and the cohesion of Christendom, the systematic accumulation of knowledge about the physical world, or the ways people are governed and conceive of their commonalities with others, but it had enormous lasting effects on all three.

The story of the Protestant Reformation starts with Martin Luther, a fiery priest and theologian angry about the Church’s selling of indulgences. (An indulgence was an expensive official forgiveness of the sins of a deceased loved one, believed to shorten their soul’s time in Purgatory.) In 1517, Luther wrote his Ninety-five Theses critiquing the crass-but-lucrative practice. In subsequent years he and others who joined the cause penned dozens of texts, extending his initial arguments into a broader attack on the Church. They ultimately persuaded millions that Luther was right and the Church was wrong, permanently fracturing Christendom.

Before the printing press, the Church could communicate far more widely and effectively than any individual, group, or institution, which enabled it to crush dissent whenever necessary. A century before the Ninety-five Theses, in 1415, the Church deemed preacher Jan Hus’ critique of indulgences to be heresy, and burned him at the stake. Hus didn’t have printers to spread his ideas, but Luther did, and the printers had strong financial incentives to spread them far and wide. Printing was a difficult, speculative business and printers needed texts that would sell in large enough quantities to cover the significant up-front labor cost of setting the type for each book or pamphlet, and also earn a return on their capital investments in presses and buildings. Brother Luther’s sharp tongue helped printers find and cultivate a large market for his attacks and those of others who waded into the rhetorical brawl that became the Reformation.

The combination of the printing press and a large market for its products allowed Luther and others to confront the Church on a level playing field. Rather than being executed for heresy like Jan Hus, their efforts sparked a clash of theological ideas that split Christendom and threw Europe into a state of violent upheaval for much of the next 130 years.

In addition to its many discoveries in chemistry, physics, astronomy, and biology, the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries led to the rise of scientific thinking, which, as much as any development in history, built the world we live in today. As historian Elizabeth Eisenstein showed in her classic The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, the Scientific Revolution was enabled by the way the printing press, in producing multiple copies of the same text, had the effect of “fixing” information, or making it permanent. Up to that point in history, knowledge tended to degrade over time. Books could be destroyed by floods or fire, or lost through human mishap. More frequently, the difficulty of replicating texts by hand – especially highly technical ones – introduced mistakes, causing bits of knowledge to leak from each successive copy.

The printing press eliminated this weakness in two ways. First, printing many copies of books at a time ruggedized the ideas and information contained in them. If one copy burned in a fire and another was ruined in a flood, there were others, so the ideas were safe. Second, it enabled a process for correcting mistakes. If a print run of a given text contained errors, readers could and did notify the printer, allowing the mistakes to be fixed in subsequent runs. This replaced the gradual degradation of knowledge with a feedback loop that sharpened and perfected it. As Eisenstein put it, “Typographical fixity is a basic prerequisite for the rapid advancement of learning.”

This subtle effect of the printing press on the durability of information was an essential condition for the accumulation and compounding of scientific knowledge in the centuries to come.

Before humanity was organized into nation-states, Europeans were governed by a mix of cities, kingdoms, and duchies, often within sprawling empires, all under the umbrella of the Catholic Church. Many smaller polities meant many different peoples speaking different languages within distinct local cultures. That’s how things were before the printing press was invented and the business of printing exploded.

In order to sell texts in the large quantities necessary to cover the fixed cost of setting the type, printers targeted the largest markets they had ready access to, which meant printing books in the most widely spoken language in their area. As printing became more common, reading did, too. The desire to read books motivated people to learn the dialect in which books in their area were usually printed. This started a feedback loop: as more books were printed in a popular dialect, more people learned it, which led to more books being printed in it, and so on until Europe’s many local languages consolidated into a handful that were widely spoken.

As previously separate peoples began to speak the same language and read the same books, a sense of affinity emerged. These groups grew more cohesive over time as the books they read gave them not only a shared cultural canon, but also increasingly similar understandings of the world. Benedict Anderson described this as the emergence of “imagined national communities.” With these building blocks in place, nation-states began to form in the 17th and 18th centuries, and by the 20th they were the dominant form of political structure in the world. Nation-states are so engrained in our mental model of the world it’s hard to conceive of things being any other way.

What stands out in these examples is how the second and third order effects of a seemingly straightforward technological capability – printing multiple copies of a text – changed the world in deep, structural ways.

Mass-produced texts plus a thirsty market allowed a theological critic to broadcast his ideas as widely and effectively as the Church, triggering a continent-wide religious free-for-all that split Christendom.

The ability to replicate texts accurately and correct errors in sequential print runs let knowledge accumulate rather than degrade, powering the development of modern science.

Books printed in popular dialects motivated people to learn those dialects, creating a feedback loop that resulted in large populations speaking the same languages and reading the same books, leading to the emergence of nation-states.

Going back to Postman, the printing press had these immense impacts across vast and varied swathes of society because it disrupted the previous equilibrium in the ecosystem of European life. Once the political, social, educational, and religious context was knocked out of balance, the system sought a new equilibrium.

You can read the whole post here. If you think it’s interesting, or even just correct (!), I hope you’ll share it.

Ecosystems, disturbed equilibria, and the chaotic process of out-of-balance systems seeking new steady states – these ideas are critical to making sense of the world in this often disorienting era.

My Work

See above.

Interesting Reads

Officials fear ‘complete doomsday scenario’ for drought-stricken Colorado River (link)

The only outlet for Colorado River water from the dam would then be a set of smaller, deeper and rarely used bypass tubes with a far more limited ability to pass water downstream to the Grand Canyon and the cities and farms in Arizona, Nevada and California. Such an outcome — known as a “minimum power pool” — was once unfathomable here. Now, the federal government projects that day could come as soon as July.

Tweets of the Week

Extreme Weather Watch

(45 degrees Celsius is 113 degrees Fahrenheit)

Creeping Fascism Watch

Progress Joy and Hope

This is more like a bandaid than a solution (though it depends on the design assumptions that went into the reconstruction), but it still matters that destroyed infrastructure doesn’t stay destroyed and we aren’t helpless bystanders: