The printing press changed everything, so will the internet

Ecological change is gradual but boundless

My last two posts, Meta-messages and the Internet, Parts 1 and 2, were about the competitive dynamics, incentives, and resulting meta-messages of the pre-internet and internet media ecosystems. Here, we’ll explore the impacts of an earlier communications technology, the printing press, and ask what it suggests about the trajectory of the internet age.

In 1998, at a conference of religious leaders in Denver, renowned media ecologist Neil Postman gave a talk called Five Things We Need to Know About Technological Change. For the fourth of his five items, he observed: “Technological change is not additive, it is ecological.” He went on,

I can explain this best by an analogy. What happens if we place a drop of red dye into a beaker of clear water? Do we have clear water plus a spot of red dye? Obviously not. We have a new coloration to every molecule of water. That is what I mean by ecological change. A new medium does not add something; it changes everything. In the year 1500, after the printing press was invented, you did not have old Europe plus the printing press. You had a different Europe. After television, America was not America plus television. Television gave a new coloration to every political campaign, to every home, to every school, to every church, to every industry, and so on.

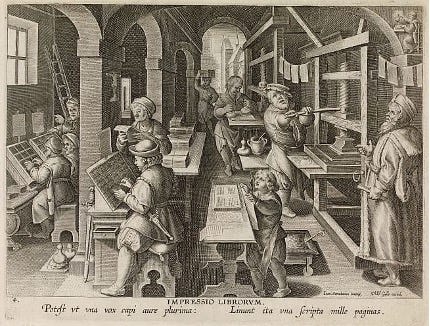

It’s no accident Postman referenced the printing press, the first technology to enable large scale one-to-many communication, in a speech given in the early years of the consumer internet, the first technology to enable large scale many-to-many communication. As we will see, the printing press had an utterly transformative effect on the world. It was arguably the crucial, and at least an essential, ingredient in bringing about no less than the Protestant Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, and the modern nation-state.

Notably, none of these consequences of the printing press were anticipated. They resulted from second and third order effects that seem, at first glance, completely unrelated to the technology itself. The capability to print multiple identical copies of a text isn’t obviously connected to Papal authority and the cohesion of Christendom, the systematic accumulation of knowledge about the physical world, or the ways people are governed and conceive of their commonalities with others, but it had enormous lasting effects on all three.

The story of the Protestant Reformation starts with Martin Luther, a fiery priest and theologian angry about the Church’s selling of indulgences. (An indulgence was an expensive official forgiveness of the sins of a deceased loved one, believed to shorten their soul’s time in Purgatory.1) In 1517, Luther wrote his Ninety-five Theses critiquing the crass-but-lucrative practice. In subsequent years he and others who joined the cause penned dozens of texts, extending his initial arguments into a broader attack on the Church. They ultimately persuaded millions that Luther was right and the Church was wrong, permanently fracturing Christendom.

Before the printing press, the Church could communicate far more widely and effectively than any individual, group, or institution, which enabled it to crush dissent whenever necessary. A century before the Ninety-five Theses, in 1415, the Church deemed preacher Jan Hus’ critique of indulgences to be heresy, and burned him at the stake. Hus didn’t have printers to spread his ideas, but Luther did, and the printers had strong financial incentives to spread them far and wide. Printing was a difficult, speculative business and printers needed texts that would sell in large enough quantities to cover the significant up-front labor cost of setting the type for each book or pamphlet, and also earn a return on their capital investments in presses and buildings. Brother Luther’s sharp tongue helped printers find and cultivate a large market for his attacks and those of others who waded into the rhetorical brawl that became the Reformation.2

The combination of the printing press and a large market for its products allowed Luther and others to confront the Church on a level playing field. Rather than being executed for heresy like Jan Hus, their efforts sparked a clash of theological ideas that split Christendom and threw Europe into a state of violent upheaval for much of the next 130 years.

In addition to its many discoveries in chemistry, physics, astronomy, and biology, the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries led to the rise of scientific thinking, which, as much as any development in history, built the world we live in today. As historian Elizabeth Eisenstein showed in her classic The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, the Scientific Revolution was enabled by the way the printing press, in producing multiple copies of the same text, had the effect of “fixing” information, or making it permanent. Up to that point in history, knowledge tended to degrade over time. Books could be destroyed by floods or fire, or lost through human mishap. More frequently, the difficulty of replicating texts by hand – especially highly technical ones – introduced mistakes, causing bits of knowledge to leak from each successive copy.

The printing press eliminated this weakness in two ways. First, printing many copies of books at a time ruggedized the ideas and information contained in them. If one copy burned in a fire and another was ruined in a flood, there were others, so the ideas were safe. Second, it enabled a process for correcting mistakes. If a print run of a given text contained errors, readers could and did notify the printer, allowing the mistakes to be fixed in subsequent runs. This replaced the gradual degradation of knowledge with a feedback loop that sharpened and perfected it. As Eisenstein put it, “Typographical fixity is a basic prerequisite for the rapid advancement of learning.”

This subtle effect of the printing press on the durability of information was an essential condition for the accumulation and compounding of scientific knowledge in the centuries to come.

Before humanity was organized into nation-states, Europeans were governed by a mix of cities, kingdoms, and duchies, often within sprawling empires, all under the umbrella of the Catholic Church. Many smaller polities meant many different peoples speaking different languages within distinct local cultures. That’s how things were before the printing press was invented and the business of printing exploded.

In order to sell texts in the large quantities necessary to cover the fixed cost of setting the type, printers targeted the largest markets they had ready access to, which meant printing books in the most widely spoken language in their area. As printing became more common, reading did, too. The desire to read books motivated people to learn the dialect in which books in their area were usually printed. This started a feedback loop: as more books were printed in a popular dialect, more people learned it, which led to more books being printed in it, and so on until Europe’s many local languages consolidated into a handful that were widely spoken.3

As previously separate peoples began to speak the same language and read the same books, a sense of affinity emerged. These groups grew more cohesive over time as the books they read gave them not only a shared cultural canon, but also increasingly similar understandings of the world. Benedict Anderson described this as the emergence of “imagined national communities.” With these building blocks in place, nation-states began to form in the 17th and 18th centuries, and by the 20th they were the dominant form of political structure in the world. Nation-states are so engrained in our mental model of the world it’s hard to conceive of things being any other way.

What stands out in these examples is how the second and third order effects of a seemingly straightforward technological capability – printing multiple copies of a text – changed the world in deep, structural ways.

Mass-produced texts plus a thirsty market allowed a theological critic to broadcast his ideas as widely and effectively as the Church, triggering a continent-wide religious free-for-all that split Christendom.

The ability to replicate texts accurately and correct errors in sequential print runs let knowledge accumulate rather than degrade, powering the development of modern science.

Books printed in popular dialects motivated people to learn those dialects, creating a feedback loop that resulted in large populations speaking the same languages and reading the same books, leading to the emergence of nation-states.

Going back to Postman, the printing press had these immense impacts across vast and varied swathes of society because it disrupted the previous equilibrium in the ecosystem of European life. Once the political, social, educational, and religious context was knocked out of balance, the system sought a new equilibrium.

Like Europe in the 1500s, America in the 2020s is a societal ecosystem that’s been knocked out of balance by a new communications medium. The history of Europe after the printing press suggests we should not expect the future of the internet age to be continuous with the past. Rather, we should expect transformative change to continue, for good and ill. The coming decades will be increasingly unpredictable, full of new opportunities and novel, unseen risks.

I want to acknowledge here that the perspective I’m articulating will unsettle and frighten some people, perhaps including you. I’m very familiar with those feelings, having lived with them for most of the past five years. The good news is that starting to see the larger forces at work can be liberating. It lets us shift from clinging to what’s slipping away to accepting our reality and thinking about what we build next.

As always, feel free to share your thoughts, reactions, questions, worries, hopes, etc. in the comments or by replying to this email.

If you [yes, you! :)] know someone who might find Destabilized thought-provoking, please do forward the email to them. Thanks!

--

Notes:

https://web.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/classes/188/materials/postman.pdf

https://www.twelvebooks.com/titles/patrick-wyman/the-verge/9781538701171/

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/printing-revolution-in-early-modern-europe/85AE910ACCCFCE8C068DDA911990AEFC

https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P8014.html

https://www.versobooks.com/books/2259-imagined-communities

Purgatory was considered, by Luther and others at the time, to be theologically dubious.

Between just 1518 and 1520, printers sold three-hundred thousand copies of Luther’s texts.

This effect was helped by the size of the book market. In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson called them “the first modern-style mass-produced industrial commodity,” with as many as two-hundred million printed in the 16th century.