Destabilized Saturday Edition #51

The slow boring of hard boards, a shit show to behold, Sarah Palin ripples, "It's a magical world, let's go exploring!"

Three stories this week reveal the fundamental challenge of climate adaptation: adaptation initiatives require spending money now for a benefit in the future, and often address risks that haven’t yet manifested fully and therefore feel far off.

The first was this New York Times story, “A Toxic Stew on Cape Cod: Human Waste and Warming Water,” which describes what’s happening on the Cape as nitrogen and phosphorus from septic systems leak into groundwater, streams, and ponds.

[T]he encrusted remains of ribbed mussels, choked in gray-black goo that smelled like garbage and felt like mayonnaise. The muck on the bottom of the Mashpee River gets deeper every year, suffocating what grows there. It came up to Ms. Fisher’s waist. …The muck is what becomes of the poisonous algae that is taking over more of Cape Cod’s rivers and bays each summer.

…The algal explosion is fueled by warming waters, combined with rising levels of nitrogen that come from the antiquated septic systems that most of the Cape still uses. A population boom over the past half-century has meant more human waste flushed into toilets, which finds its way into waterways.

More waste also means more phosphorus entering the Cape’s freshwater ponds, where it feeds cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue-green algae, which can cause vomiting, diarrhea and liver damage, among other health effects. It can also kill pets.

Septic systems are common in places where population density is too low to justify the cost of running sewer pipes to most homes. And they’re simple; a septic system is:

a box in the ground [that] holds whatever is flushed down a toilet. Solid waste settles at the bottom and is physically sucked out every few years. Liquid waste is sent into the ground, where gravity pulls it through the soil, removing harmful bacteria before it reaches the water table below. …But they don’t filter out nitrogen or phosphorus, which seeps into the groundwater and, eventually, bodies of water.

Clearly, something has to be done. The main options are:

Mandating that homeowners install a high-end septic tank that filters out Nitrogen (paid for directly by each homeowner); or

Build or extend municipal sewer systems so they reach most houses (paid for by local taxes, which are paid by homeowners).

The problem is both options are very expensive. This leaves Massachusetts and Cape Cod leaders in a predicament, one that will become increasingly familiar in the years ahead. On one hand, the problem must be addressed, and soon; on the other hand, the potential solutions are so expensive some residents won’t be able to afford the upgrades and may have to move.

—

Another story, this one in High Country News, looks at Oregon homeowners’ angry response to their state’s new wildfire risk maps.

In July, a thin white envelope appeared in 150,000 Oregon mailboxes, with a short letter inside that sparked a statewide controversy. The Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) was assigning wildfire risk levels to property, and residents in high or extreme risk areas and in the wildland-urban interface — where development and flammable vegetation collide — would likely become subject to new building codes and standards for creating defensible space.

For states out west, preventing structures from burning is crucial so the adaptation imperative for Oregon is straightforward, just as it is in Cape Cod. But plenty of Oregonians don’t want to spend money they weren’t planning to spend and may not have. The response to the new wildfire risk maps was predictable:

Many railed against the designations, calling them government overreach. …In public meetings, state officials and residents talked past one another. Agency staff provided technical explanations about how the map was created, while citizens wanted specifics on its implications. “This is going to hurt me,” one woman said in a public meeting. “It’s going to hurt my property; it’s going to hurt my family.”

The struggle was eventually translated into our familiar red/blue political divisions, which is partly a reflection of today’s political climate. It’s also a reflection of tensions and mistrust between blue state legislators and exurban and rural residents. The latter group will be most affected by wildfire risk maps because they are more likely than urban or suburban residents to live near the wildland-urban interface. But even without any preexisting political mistrust or animosity, a subset of people will always react angrily and push back hard when the government demands they spend money to protect against something that may not happen for years.

—

The final story, from ProPublica, is about Colorado’s failure to update building codes and other regulations to account for wildfire risk following the shocking Marshall fire in late 2021 that killed two and burned more than 1,000 houses in a Boulder suburb.

[D]espite previous warnings of this new threat, ProPublica found Colorado’s response hasn’t kept pace. Legislative efforts to make homes safer by requiring fire-resistant materials in their construction have been repeatedly stymied by developers and municipalities. …Many residents are unaware they are now at risk because federal and state wildfire forecasts and maps also haven’t kept pace with the growing danger to their communities. Indeed, some wildland fire forecasts model urban areas as “non-burnable,” even though the Marshall Fire proved otherwise.

Developers don’t want it to be more expensive to build and municipalities don’t want to cede control of building codes to the state. Because there’s not a similarly focused, motivated constituency for this prudent public policy, those two interest groups have thus far succeeded in preventing climate-aware building regulations from becoming law.

—

The common thread in these three stories – and indeed, in all climate adaptation efforts – is that costs are incurred now while the benefits are in the future. That means every climate adaptation policy defines its own opposition. The famous Max Weber line, “Politics is the slow boring of hard boards,” perfectly describes the political challenge of ruggedizing our communities for the realities of a changing planet.

My Work

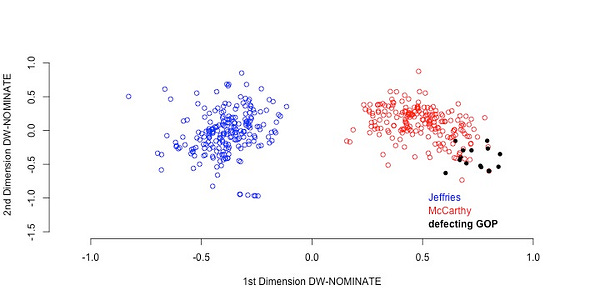

[In recognition of the House Republican radicals’ attention war victories this week.]

The internet and the attention war (link)

Like the pre-internet media, today’s media ecosystem isn’t the result of design or intention. Rather, it emerges from millions of independent actors assessing incentives and pursuing their self-interest:

Content creators, wanting to capture people’s attention, learn what works & do more of it.

Readers and viewers, seeking entertainment, distraction, meaning, and belonging, find and consume content that speaks to them.

Unfortunately, the content styles best at driving the engagement creators crave turned out to be material that incites anger and provokes outrage. As a result, what emerges from today’s media ecosystem is a meta-message of disunity.

Interesting Reads

[This is a PBS News Hour video (+ transcript); the most interesting part is 5:43 to 7:00.]

Mismanagement complicates Pakistan’s long recovery from deadly floods (link)

Four months after a third of the country was underwater, Pakistan is still struggling to recover. The disaster affected more than 30 million people and is seen as a warning for other climate-vulnerable countries. As Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, recovery in the short and long term present complex challenges.

Tweets of the Week

Extreme Weather Watch

Creeping Fascism Watch

Really great post! What a great newsletter! I don't really get into politics anymore.. it's too demoralizing, but after watching on C-SPAN every single minute of the show in the House this week, I'd say that we have to make a clear distinction between politics and governing. What I saw was a lot of politicing and very little concern with governing. Politics is simply factionalism and it's a plague in the House. Governance is a sober, non passionate skill seemingly in short supply there. I wouldn't mind if we banned all politicians from the House and got rid of that silly division into two sets of seats, in perpetual opposition and incapable of working, just like two locked gears. A House populated with robots would even be preferable!