From Eisenhower to Trump

How the post-war transformation of the major party coalitions created today's divisions

In the 1950s, the Democratic Party coalition – FDR’s New Deal coalition – was larger than the Republican coalition and controlled Congress, usually by large margins, for most of the 60 years from 1932 to 1994.

But because the Democratic Party was highly culturally, regionally, and ideologically diverse, it often struggled to nominate presidential candidates that could appeal to the whole coalition. As a result, from 1952 through 1988 Republicans won 7 of 10 presidential elections.

The parties in the 1950s had significant overlap. There were liberals and conservatives who were Republicans, and liberals and conservatives who were Democrats. Both parties reflected the country in other ways, too, including being overwhelmingly white and Christian, and the vast majority of adults being married. American politics was so unpolarized that the American Political Science Association (APSA), in a report called Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System, argued that it was important for the country to have more ideologically distinct parties. APSA’s argument, rooted in democratic theory, was that when the major parties in a two-party system are highly similar, voters can’t easily align their vote with the policies and programs they prefer. The less clear the parties’ brands, the harder it is for people to cast informed votes.

So how did we get from the homogeneous quasi-unity of the 1950s to the sharp-edged polarization of today?

The Republican Party was formed in 1854 specifically to oppose slavery, and the Union Army that destroyed the institution of slavery was commanded by the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln. So when the 15th Amendment made it legal for Black men to vote, it wasn’t surprising an overwhelming majority voted Republican. Black former Congressman John R. Lynch (R-MS) conveyed the view many older Black voters held into the 1930s:

The colored voters cannot help but feel that in voting the Democratic ticket in national elections they will be voting to give their endorsement and their approval to every wrong of which they are victims, every right of which they are deprived, and every injustice of which they suffer.

Black political allegiances started to shift in the 1930s and 1940s. Though neither major party endorsed legal racial equality, one was doing a bit more for Black Americans than the other, and Black voters noticed.

FDR’s New Deal programs helped Black Americans weather the Great Depression.1

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was an ally and an outspoken proponent of civil rights (despite the political complications it created for her husband).

FDR’s vice president and successor, Harry Truman, desegregated the armed forces after WWII and was the first president to address the NAACP.

The South2 was overwhelmingly Democratic for more than a century after the Civil War for the same reason Black voters were Republicans. Southern Democrats of the time were segregationists and despised the notion of racial equality. Democratic Party leaders' pro-civil rights actions caused unsustainable intra-party tensions.

Those tensions were ultimately resolved when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act into law in 1964 and 1965. This was a seminal moment in American political history, as the leader of the Democratic Party threw its lot in with Black voters and the cause of racial equality and multiracial democracy. Legend has it that as he was signing the historic voting rights bill, LBJ turned to someone next to him and said, “There goes the South for a generation.”

The major party coalitions were already evolving in the mid-1960s, but the Voting Rights Act accelerated the process and made it irreversible.

The most rigorous and comprehensive account of the 20th and 21st century evolution of the major party coalitions is The Great Alignment by Emory political scientist Alan Abramowitz. It’s worth digging into the details to see the logic and structure that drove the evolution forward.

In the 1950s, the country was 90 percent white and, because of Jim Crow, the electorate was even more so. Both would grow more diverse in the years ahead.

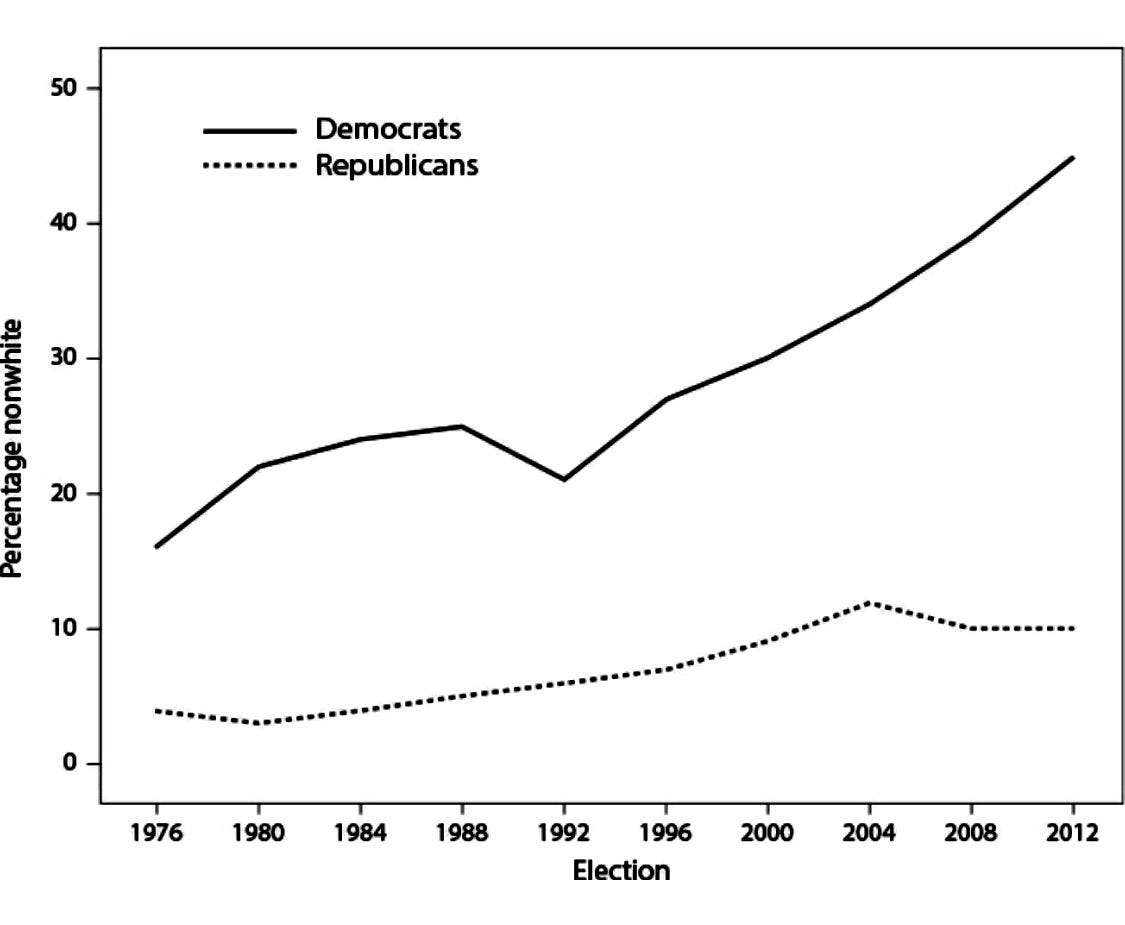

[I]n the 1952–1960 elections, both parties’ supporters were overwhelmingly white: nonwhites made up only 7 percent of Democratic voters and only 2 percent of Republican voters… [and] white southerners outnumbered nonwhites among Democratic voters by more than a three-to-one margin… By the 1984–1988 elections, nonwhites made up 29 percent of Democratic voters and 7 percent of Republican voters.

Another way to put this is that from the 1950s to the 1980s the Democratic Party went from 93 percent white to 71 percent white, while the Republican Party went from 98 percent white to 93 percent white. As this chart shows (and as we know), the trend has continued into this century.

(One thing I find charming about Abramowitz’s book is the un-fussiness of his graphics.)

The growing racial diversity of the Democratic Party wasn’t the only change taking place.

At the same time that nonwhites were becoming a much larger part of the Democratic electoral coalition, white southerners were leaving it. Among white southerners, over these three decades, a 55-point Democratic advantage in party identification turned into a two-point Republican advantage: among all southern white voters in the 1984–1988 elections, Republicans outnumbered Democrats by 46 percent to 44 percent.

The net result was:

Between the 1952–1960 elections and the 1984–1988 elections, the southern white share of Democratic voters in the nation fell from 24 percent to 16 percent, while the nonwhite share rose from 7 percent to 29 percent. In the 1952–1960 elections, white southerners outnumbered nonwhites among Democratic voters by more than a three-to-one margin; among Democratic voters in the 1984–1988 elections, nonwhites outnumbered white southerners by nearly two to one.

It’s worth reading those numbers again, because this shift has defined both major parties from the 1980s until today.

The consequences of this shift for Democratic Party leaders and candidates would eventually be profound. A combination of demographic shifts in the voting-age population and secular realignment within the electorate meant that the influence of the most conservative element of the Democratic coalition was clearly waning, while the influence of the most progressive element… was growing.

Politicians naturally responded to the changing political context within their parties.

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, Democratic presidential candidates from Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey to Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis championed civil rights legislation and social welfare programs to combat racial and economic inequality, while Republican presidential candidates from Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush courted racially and economically conservative white voters with subtle and not-so-subtle appeals to racial fears and prejudice, and with opposition to social welfare programs that many working-class whites increasingly saw as primarily benefiting nonwhites.

The rational choices of politicians reinforced the evolution of the major party coalitions, continuing the flow of more liberal and racially diverse voters toward the Democratic Party and more conservative white voters toward the Republican Party.

Divergent positions on civil rights and racial equality triggered the realignment of the party coalitions after WWII. But, crucially, it turned out voters who were liberal on racial issues tended to be liberal on other cultural issues, as well (and the reverse was true for voters who were conservative on racial issues). As more liberal-minded people gravitated to the Democratic Party based on its embrace of racial equality, Democrats naturally became the party that more enthusiastically and universally embraced other liberation movements of the late 20th and 21st centuries, including women’s rights, gay rights, Muslim civil liberties, immigrant rights, Indigenous rights, Trans rights, and many others. That, in turn, drew in more voters who agreed with the Democratic Party’s embrace of legal and cultural equality for all people.

And so on, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

An evolution with similar dynamics but in the opposite direction was happening at the same time within the Republican Party.

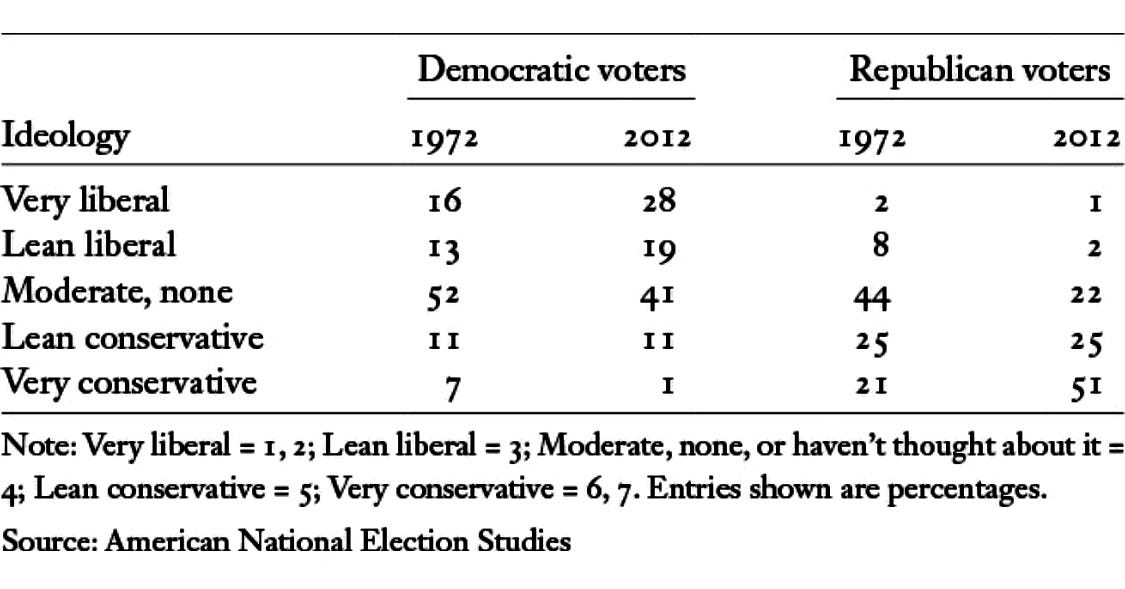

Over the 40 years from 19723 to 2012, the net effect on the ideological makeup of the two major parties looked like this:

In 1972, Democrats who were very liberal or leaned liberal were 29 percent of the party, compared with 70 percent who were moderate to very conservative. By 2012, liberals had achieved near-parity, at 47 percent to 53 percent moderate and conservative.

Similarly, in 1972, Republicans who were very conservative or leaned conservative made up 46 percent of their party, compared to 54 percent who were moderate to very liberal. Forty years later, conservatives accounted for 76 percent of the party compared to just 25 percent who were moderate or liberal.4 (It was in the 2012 Republican presidential primaries when Mitt Romney described his tenure as Massachusetts governor as “severely conservative.”)

Though it’s not shown in this data, the trend has persisted since 2012.

The two major parties have gone from so similar in 1950 that it made political scientists uncomfortable, to being different in almost every politically-salient way.

The story I’m sharing today is not anything close to the full story. That version includes Republican cultivation of evangelical protestants following Roe v. Wade in 1973, the coordinated response of big business to the liberal consensus of the 1960s, the decline of labor unions, the rise of gun culture, the mechanization and disappearance of decent-paying physical jobs, and more.

But the full version ends in the same place as this shorter version: contemporary American politics is highly polarized along lines of not just race and ideology, but also religion, gender, age, region (urban/rural), and education. Political scientist Lilliana Mason calls the political identities that result from stacking multiple primary dimensions of identity, mega-identities.

It’s the opposite condition of the the state of play in the 1950s where both political parties contained wide ranges of ideologies, regions, religions, etc. As APSA worried, parties that are too close together lead to problems, but parties that are too far apart – i.e. polarized – create a different and potentially more dangerous set of problems.

The seeds of these problems live in the perceptions of voters. For example, Americans now rate presidents of the other party far more negatively than we used to.

And voters describe themselves as more ideologically distant from the other party than they did several decades ago.

Today, the ideologies and partisanship of states are much more tightly connected today than they used to be. (Anecdata: when I worked in the Senate in 1999-2000, all 4 senators from the Dakotas were Democrats.) In one way, this is a straightforward symptom of the alignment of party and ideology, but in another way it shows how politics has enveloped more and more domains of life. Being a Democrat or a Republican said little about you in 1950; in 2022, it says a lot about you.

Polarization makes it harder to relate to a group of people who we see as – and who actually are in many respects – different from us. This tends to breed distrust and erodes the ability to communicate across the aisle. It also makes it easier to get attention, score political points, and build power by taunting and belittling the other side, and by reacting to their outrages with ostentatious fury.

To close, I want to offer an observation.

In recent years, pundits have frequently identified the late 1960s as the last period in U.S. history as turbulent as the early 2020s. This is probably true, and yet it misses something important. When we compare the instability of 2020-2022 with the instability of 1968-1970, there are two key differences.

First, in 1968, it was still early in the evolution of the major party coalitions, which meant the parties still had considerable ideological, racial, religious, and geographic overlap. Those similarities and affinities provided the raw material for compromise and coordinated action, as, for example, when a group of powerful Republican senators in 1974 famously told Nixon to resign or face impeachment and conviction.

Second, the media ecosystem in 1969 was dominated by newspapers and television, which were incentivized to offer centrist and unifying national narratives. As I wrote in Meta-messages and the internet, part 1:

A lot of safe, broad-appeal news and programming reinforced the ideas of the American story: the country belongs to all of us, we all have a stake, and we’re in this together. Generations of popular TV shows like Happy Days, Family Ties, The Wonder Years, and more, as well as newspapers and local and national TV news programs, delivered a consistent meta-message of decency and unity among good Americans. This was the narrative air we breathed for the 50 years between World War II and the rise of the consumer internet in the mid-1990s.

…Another feature of the pre-internet media was that everyone consumed it in the same window of time. In his classic book, Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson called daily newspapers “one-day bestsellers”; the paper was only valuable for a day so that’s when people read it. Similarly, the six o’clock news and prime time TV were only on when they were on, so everyone watched them at the same time. Because there were just one or two local papers and three TV stations, as each person was reading or watching they knew their neighbors were, too. In a tangible sense, people consumed these stories together, and this element of community ritual reinforced the unity meta-message of the content.

Exactly how much these two unifying forces helped the U.S. in the 1960s constrain and reverse rising disorder, and ultimately pull out of a period of unrest and instability, is hard to know. But both forces were powerful so the combined effect was likely significant.

Today, these structural bonding forces are gone. They have been replaced by two polarized political coalitions, nearly as different as they can be, and an internet media ecosystem that incentivizes antagonistic, cruel, and even threatening rhetoric.

As a result, we’re in a weaker position as a country, with fewer tools available to respond to potential upheaval.

Notes

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Party_divisions_and_control_of_the_house_and_senate.pdf

https://www.jstor.org/stable/i333592

https://www.amazon.com/Uncivil-Agreement-Politics-Became-Identity/dp/022652454X/ref=as_li_ss_tl

https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Keeping-the-Faith/Party-Realignment--New-Deal/

https://www.npr.org/2017/05/03/526655831/a-forgotten-history-of-how-the-u-s-government-segregated-america

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300207132/great-alignment

Though they were often administered in a discriminatory manner, including the Federal Housing Administration’s notorious system of redlining, which, by refusing to ensure mortgages in and around areas where Black families lived, led to the destruction of vast amounts of Black wealth.

The area first settled by English slavers leaving Barbados seeking more land for sugar plantations.

The first year the American National Election Studies (ANES) asked voters about ideology was 1972.

Doesn’t add to precisely 100% because of rounding.