Insurance companies are climate change truth-tellers

Politicians can ignore climate reality, the insurance industry can't

Insurance is an enabler of economic activity. Lots of things we do, from flying airplanes to shipping goods to building structures, wouldn’t be possible at scale if there was a chance of a catastrophic economic loss. By taking on and pooling together, in exchange for fees, expensive-but-unlikely risks, the insurance industry guarantees that if disaster strikes the relevant market actor will okay. As long as these risks are diversified and the fees insurers charge are adequate, this is not only a socially valuable service but also a profitable one. By mitigating risk and thus facilitating economic activity, insurance is a pillar of modern prosperity.

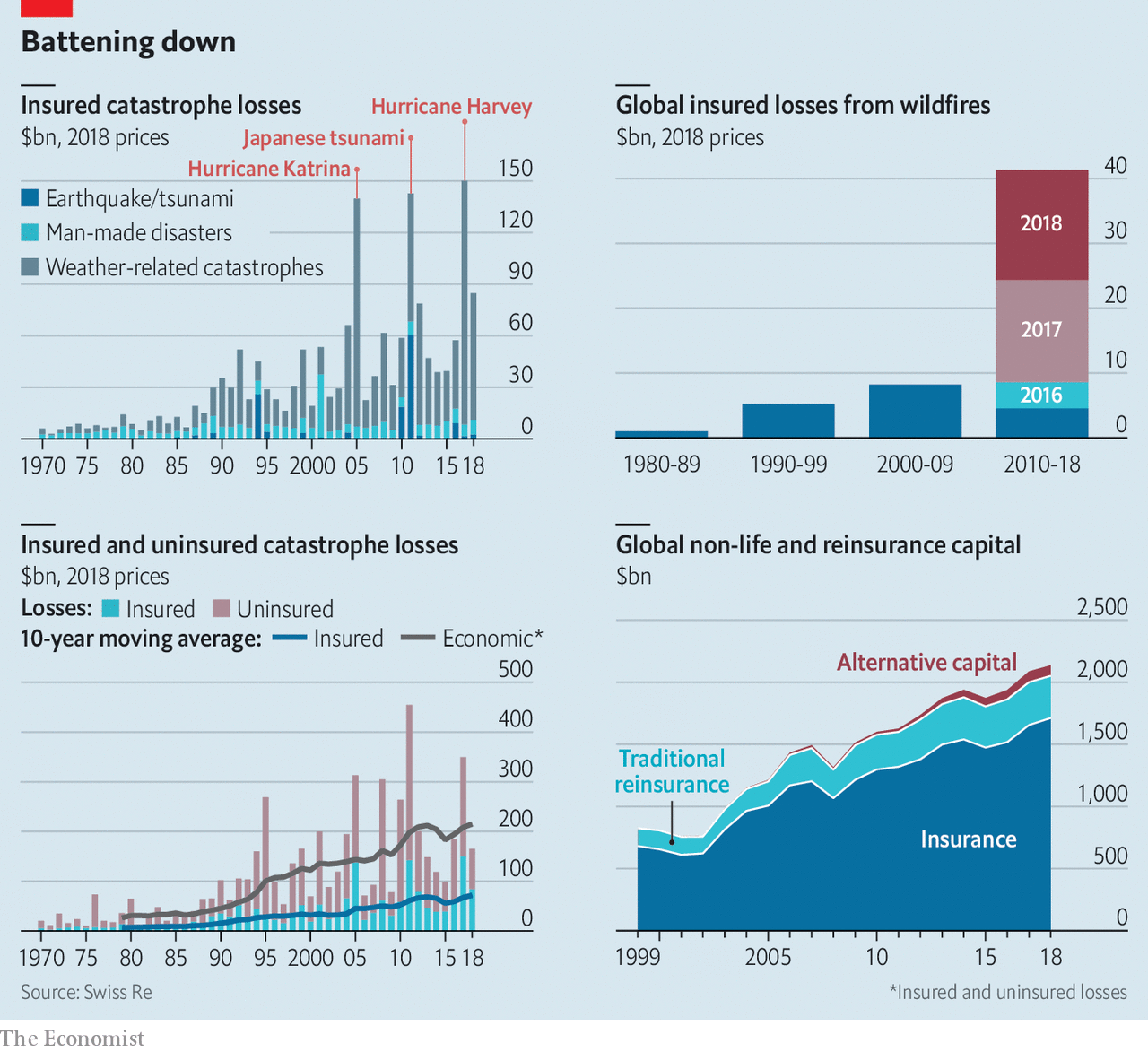

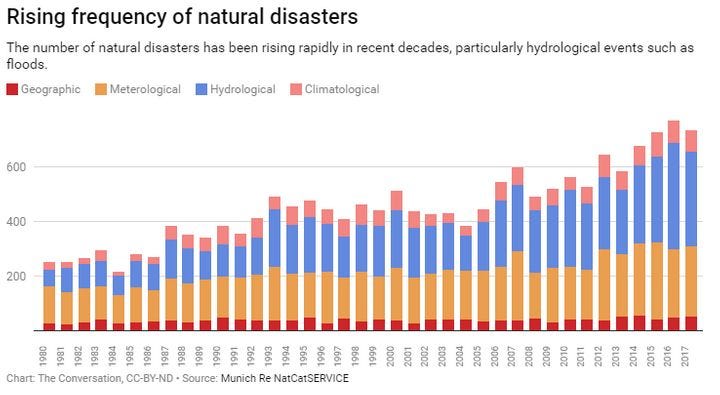

But the insurance industry and the invaluable role it plays in the world is being significantly affected by growing risks from climate-fueled extreme weather events. That in turn is hitting homeowners and others with higher prices. Insurance is a key piece of the climate transformation story and this edition of Destabilized is my effort to understand how the industry works, how climate change is affecting it, what we can learn about climate risks from insurance pricing, and what it all means for the future.

Every insurance policy is one bet in a portfolio of bets made by an insurance company. For the company to succeed, the sum of all the premiums paid by its portfolio of policies (bets) need to exceed the total amount paid out in damages.1 Any one policy may require the company to pay out a lot more than it takes in – for example, if someone with a good driving record who pays $80 per month in car insurance hits some black ice and crashes their 4-month-old new car into a tree – and that’s fine, as long as it’s offset by enough policies that pay premiums without incurring damages such that total revenue from the portfolio exceeds total payouts.

To ensure portfolio revenues exceed costs, insurance companies have to charge premiums that accurately reflect underlying risk.2 The riskier a policy, the higher the price required to make it a sound bet.

One insight from this stylized analysis of the insurance business3 is that insurance companies can insure both low-risk customers and high-risk customers simply by charging each a price that reflects the underlying risk. Doing so profitably is relatively straightforward when insured activity is taking place in a steady state context, but much harder when the context is in a period of upheaval and uncertainty.

—

Before we go too far, let’s define a foundational term. Risk, as I’m using it here, is the likelihood of something happening multiplied by its cost if it does happen. This gives us what we can call the “expected cost,” which is analogous to the economic concept of “expected value” (outcome value times outcome probability). For example, if a major hurricane has a 4 percent chance of happening in a given place in a given year, and, if it happens, would completely destroy a $600,000 home, the annual risk to the home is 4% * $600,000 = $24,000. So the policy should cost $24,000 (plus, in the real world, an amount on top of that to cover operating costs and profit). If an $800,000 house in a different place has a a 0.5 percent chance of getting hit by a major hurricane, the risk to be insured is 0.5% * $800,000 = $4,000, so that’s what the policy premiums should be.4

To review: in the insurance business, premiums (i.e. price) must match risk. The order of activities is: determine risk —> set price. It’s great for the insurance company if price is higher than risk, but a competitive market for insurance services makes that hard to pull off. If price is less than risk, however, an insurance company becomes a financial time bomb that will explode when the events they have under-priced eventually occur.

—

In a moment I will offer some observations about insurance in the climate change era, but first let’s talk about four other relevant features of the insurance business:

Competitive markets – Insurance is an industry with multiple companies who compete for customers in several ways, including on brand/trust, quality of service, ease of sign-up and use, and especially price. The competitiveness of the market and consumers’ focus on price means insurance companies’ profit margins are typically low.

Revenues now, costs later – In most businesses, costs are incurred before revenues: raw materials, equipment, and other inputs are purchased, they’re transformed into products, and eventually they’re sold. Costs first, revenues later. But in insurance, the product is sold and revenue collected up-front and ongoing, and only later is the product – payouts of claims – delivered to (an unlucky subset of) customers.5 Revenues first, costs later. As insurance icon Warren Buffett says, the product insurance companies sell is a promise. It’s the promise that if someday a customer encounters bad fortune, the insurer will step in, pay for what’s covered, and in so doing protect the customer financially.

Diversification – As I alluded above, the key to insurance companies being able to keep the promises they make is to have their portfolio of policies/bets be highly diversified. Take an extreme example where an insurance company has just one customer who buys auto insurance for $100/month. If that customer gets in an accident after 8 months, in which a $30,000 car is totaled, the insurer will only have collected $800 to put toward the claim and therefore won’t be able to keep its promise. Similarly, if a property insurer has millions of customers around the world, claims stemming from a hurricane in Florida can be easily paid. But if another company insures property only in Florida, then a major hurricane my drive the insurer into bankruptcy.6

Highly regulated – Insurance is a highly regulated industry at the state level. If it weren’t, we would see at least some insurance companies taking in premiums, paying out big bonuses to its executives, and then not having enough cash to pay out claims down the road. The insurer would go bankrupt and the executives would walk away rich. (There’s a potential principal-agent issue in insurance that lies just below the surface. As I understand it, it’s mostly mitigated by state regulations that mandate minimum levels of financial resilience, including by requiring companies to hold cash and liquid investments in certain proportion to their insured risks.)

The above features and dynamics of the insurance industry pre-dated the climate era, but climate change is complicating things further. As I mentioned, assessing risk and pricing insurance is easy when times are placid and more difficult in periods of churn like the one we’re in now. But it’s even more complex worse than that. As I wrote in Are Miami real estate buyers crazy, or am I?, damage to the built environment caused by climate-fueled extreme weather grows nonlinearly. From Texas A&M Atmospheric Sciences professor Andrew Dessler:

[I]f you're wondering why climate impacts seem to be getting much worse suddenly, let me introduce you to the concept of non-linearity. In a linear system, things change in straight line. If climate impacts are linear, then every 0.1°C of warming would give you the same amount of damage. In a non-linear world, on the other hand, every 0.1°C of warming produces larger damage than the previous 0.1°C. The reason for the non-linearity of climate impacts is that individuals and communities are impacted by climate when it passes thresholds. With 1.1°C of global-average warming, we are departing the climatic conditions that much of the infrastructure designed in the 20th century was designed for. Every 0.1°C of warming is going to push us past an exponentially increasing number of thresholds in the climate system.

This nonlinearity of climate disasters, which represent a growing share of all insured risk7, makes it hard to model climate impacts, which directly affect the risks insurance companies are asked to insure. Insurance companies have access to many of the best climate change models, but even the best models can't offer precision or guarantee accuracy.

Risk assessment is made even harder by highly competitive markets for insurance products. If insurers focus on the solemnity of selling the promise that they'll be there for their customers in times of need in the future, they may be inclined to be conservative by charging higher prices to ensure their ability to pay future claims. But that approach will enable less scrupulous companies to acquire more customers by offering lower prices. This in turn creates a danger that a growing proportion of policy holders are covered by the insurance firms least able to pay all future claims.

High integrity insurers are thus squeezed between a rock (the need to charge high enough prices to be able to keep all their promises) and a hard place (the incentive to keep prices low enough to win new customers and keep existing customers in the context of a competitive market).

—

To review, the combination of:

the competitive market for insurance, which results in low profit margins,

the revenue now, costs later model, which invites risk-taking via aggressive pricing by insurers, and

the historically unusual, rapidly and nonlinearly increasing risk due to climate change

is a growing source of strain in insurance markets. States all have public insurance safety nets, usually funded by fees assessed on all insurers, that step in when firms become insolvent. These are further backstopped by state taxpayers, who will likely end up paying out of pocket to rebuild after destructive climate-fueled weather events that cause more damage than insurers have the financial means to cover.

(There’s an important reinsurance piece of this analysis that I’ll come back to in the future. For now I’ll just say that if reinsurers continue to cover climate-driven growing extreme risks, they will make sure the premiums they charge adequately reflect the increasing likelihood of climate-fueled extreme weather events. That means whether insurance companies hold the cash themselves or pay premiums to reinsurers to protect against high-cost, low-but-growing-probability events, they will foot the bill one way or the other, and will have no choice but to pass the cost on to their customers. The only “unless” in this analysis is if state governments get so many complaints from home-owning voters about the rising cost of home insurance that they step in with state resources to keep premiums artificially low. Even that, however, is window dressing because if the state is on the hook it’s taxpayers, one way or the other, who are the ultimate backstop.)

I’m still puzzling through all of what this means, but there are at least two core truths about the nexus of insurance and climate change:

The cost of insurance, especially home and other property insurance, is heavily influenced by the severity of climate risk a property is exposed to.

The more climate vulnerable a place is, the more insurance costs will increase in the years ahead. This will directly affect our private insurance premiums and also local taxes to fund higher insurance costs for local governments.

Because it has no choice but to adjust its prices to reflect the actual underlying risks, the insurance industry is one of the most reliable truth-tellers about climate change. Put another way, the insurance business model hinges on accurate assessments of climate risks. The large number of insurer bankruptcies show us they’re far from infallible, but they have serious skin in the game and no incentives to obscure reality.

In the coming years, if you want to know where climate change is headed and how its risks are distributed geographically, look at premiums for property insurance and you’ll have a pretty good idea.

For this post, I’m going to shorthand this business equation as “taking in more than it pays out,” though in reality the amount taken in needs to exceed the amount paid out by enough to both cover its share of operating costs – employee salaries, rent, customer acquisition, computers, pens, etc. – and to turn a profit.

In another simplification, I’m assuming away the issue of important coverage details like size of deductibles, exclusions of non-covered damage, risk-mitigating actions required of the insured, etc., and focusing solely on risk and price.

Yet another simplifying assumption I’m making is to ignore the significant sums of investment income insurance companies often earn (when markets are rising, in particular) by investing accumulated premiums.

In both of these examples we’re assuming there are no other risks, which is obviously not the case but is a simplifying assumption for illustrative purposes.

Insurance is one of the only things we pay for where the luckiest customers are the ones who never get anything back in exchange. I pay monthly, and will into my mid-60s, for life insurance that I hope my family never gets any money from. (With that point made, the better way to understand insurance is that we do actually get something in exchange for our premiums: we get a guarantee that misfortune won’t bankrupt us.)

Most big national insurance firms stopped writing homeowners’ policies in Florida after Hurricane Andrew, so many Florida insurance companies operate only in that state.

Though standard home insurance does not cover flood damage, which has to be insured separately, typically through FEMA’s NFIP (comprehensive auto insurance *does* usually cover flood damage, and as we were reminded by Hurricane Ian, flooding ruins a lot of cars).