Is the world becoming more chaotic, or does it just feel that way?

Toward a more rigorous approach to the most important macro question of our time

In a piece this week titled “Is the World Really Falling Apart, or Does It Just Feel That Way?” Max Fisher of the New York Times offered a sometimes insightful but ultimately unsatisfactory analysis. It’s actually an interesting article, but I found it irritating nonetheless, partly it’s because it included only a single passing reference to climate change: “No one wants to cheer a famine that is less severe than it might have been in the past, especially not the families whom it puts at risk, and especially knowing that future conflicts or climate-related crises could always cause another.” But the article bugged me mostly because it didn’t even attempt a rigorous answer to the profoundly important question it posed.1

Understanding and answering that question and figuring out what to do about it is the mission here at Destabilized, so this is something I’ve been thinking a lot about. What I’m going to do today is simply identify the key elements that any rigorous approach to answering the question needs to include. These represent the criteria by which efforts to answer the question should be judged.

A rigorous approach to answering the question, “Is the world becoming persistently more turbulent, or does it just seem that way?” (the language tweak because I reject the casual nihilism of the phrase “falling apart”) must include two elements:

Examining whole systems and looking for structural shifts.

Projecting current dynamics into the future.

If you’re not doing these two things, you’re probably not really trying to answer the question. Let’s look at both.

Examining whole systems and looking for structural shifts

To understand whether something has changed that could lead to a persistently more tumultuous world, we have to look past discrete events and try to see the system dynamics that generate them. For example, it’s not terribly illuminating to say Trump’s election in 2016 is evidence of a more chaotic world, unless we can also explain what allowed an obviously unfit person to become president. Was it a fluky outcome, a proverbial triple-bank shot? Or was it enabled by fundamental changes in the systems through which presidents are chosen? This is the key question.

By 2016, many of the presidential nomination system’s filters, which in the past would have kept a figure like Trump out of positions of power, had lost their influence.

The internet meant journalists could no longer exercise a soft veto by refusing to cover him; in fact, because Trump was the most entertaining, journalists had to cover him to effectively compete in the permanent online attention war.

Social media in particular meant Trump could communicate directly with voters without needing the approval of political donors in order to raise money to run television ads.

To the extent Trump did need money to run ads, the internet allowed him to solicit it directly from voters, efficiently and at scale.

I analyzed these system changes in Internet incentives and GOP authoritarianism:

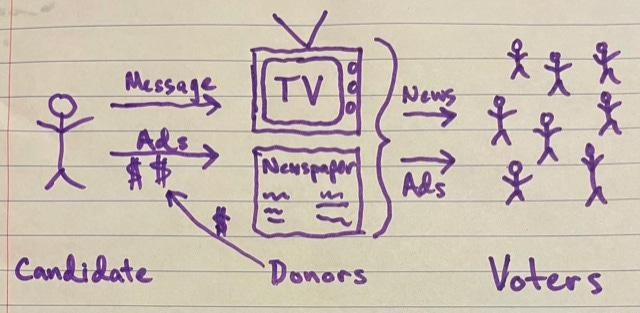

Old system: legacy communications mediums positioned campaign donors and media elites as gate-keepers between candidates and voters

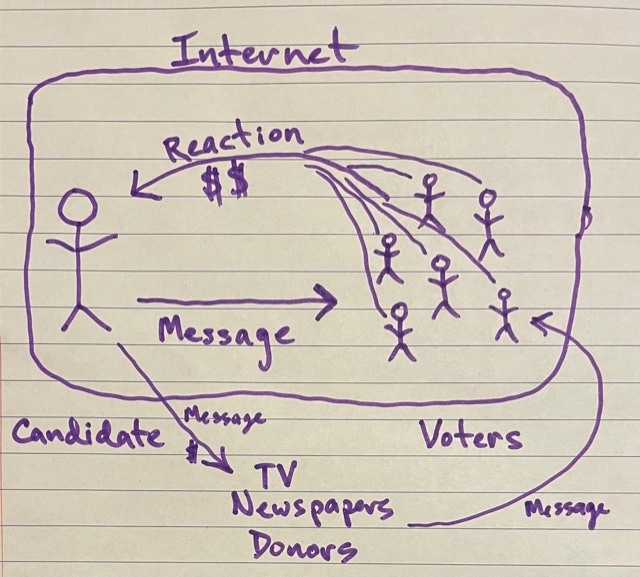

New system: the internet allows candidates to directly appeal to and fundraise from voters and activists via social media, with no intermediaries involved

The internet fundamentally altered the system through which the U.S. chooses presidents, and Trump’s election was a result of this change to the system.2 (Bernie Sanders’ almost-wins in the Democratic primaries of both 2016 and 2020 were two other near-results.3)

If the key systems in a given domain haven’t changed very much, the chaos we’ve lived through may be random or passing, but if those systems have undergone fundamental shifts, it’s far more likely increased turbulence is here to stay.

The key avenue of inquiry is whether the relevant systems have changed and if the changes can help explain the rising societal tumult.

Projecting current dynamics into the future

For the world to have entered a period of persistently greater upheaval, it must have already become more chaotic and the increased chaos must be expected to persist or increase in the future. We can’t just look back, in other words, we also have to project forward. We can think of this as a two-by-two grid with recent past on the vertical axis and the future on the horizontal. Each is divided into “yes, more turbulent” and “no, not more turbulent.” In order to say the world has become persistently more turbulent, we must be in the quadrant representing a more turbulent past and a more turbulent future.

Answering the question about the recent past – whether recent years have seen higher levels of chaos than the years further back in time – is simple, It could even be answered quantitatively by counting instances of upheaval.

Answering the question about the coming years is far more difficult, in the Yogi Berra/Niels Bohr “Predictions are hard, especially about the future” sense. But it’s absolutely necessary because if we can’t rigorously support a claim that the coming years will be at least as tumultuous as the recent past, we obviously can’t be confident we’re in a more turbulent time.

The need to project into the future is precisely why we need to analyze systems and not merely events. Only with a holistic perspective on the relevant systems can we predict what will emerge from their processes in the future.

Continuing with the presidential example, having determined that the internet fundamentally altered the system in which candidates seek their party’s nomination, we can conclude that the chances it will produce a disruptive nominee who, if they win the general election, could further destabilize the country, remains elevated and will for the foreseeable future. This is in large part because the internet profoundly changed how the system through which choose presidents works. In the political domain, then, the answer to “Is the world becoming persistently more turbulent?” is an emphatic yes.

—

Examining whole systems and looking for structural shifts, and projecting current dynamics into the future are the two key features of rigorous analyses of whether the world has become persistently more turbulent. Analyses that lack these elements are often interesting and informative, but they aren’t serious efforts to answer the question.

In fairness, it’s just one article and it’s actually pretty interesting if you focus on what it is rather than what it isn’t.

There were other changes to the system, as well, including that extreme polarization and negative partisanship have made it so any major party presidential nominee has a very real chance to win the general election regardless of their suitability.

Bernie is not a system-destabilizing sociopath like Trump, but he would have been a dramatic departure from the kinds of candidates who could and did get elected president in all of American history before 2016.

Hi Ethan - I have a number of family members who are addicted to the "extreme polarization and negative partisanship" pushed by Fox news. As Fox has proven for decades, anxiety and fear are addictive, so that is what they peddle.

In other words, it isn't just social media driving the destabilization of society, it is the closed loop of social media and dishonest television (and talk radio) media... it is Fox "news" and their ilk.

I've done the experiment of watching Fox for a week. They present an Orwellian, dystopian nightmare of disinformation and white entitlement. And they are loved and respected by at least a third of the American audience, and even more around the world.