Mega-transformations and context dependence

We need to get better at anticipating what may happen as our media-information system and earth's climate rapidly transform

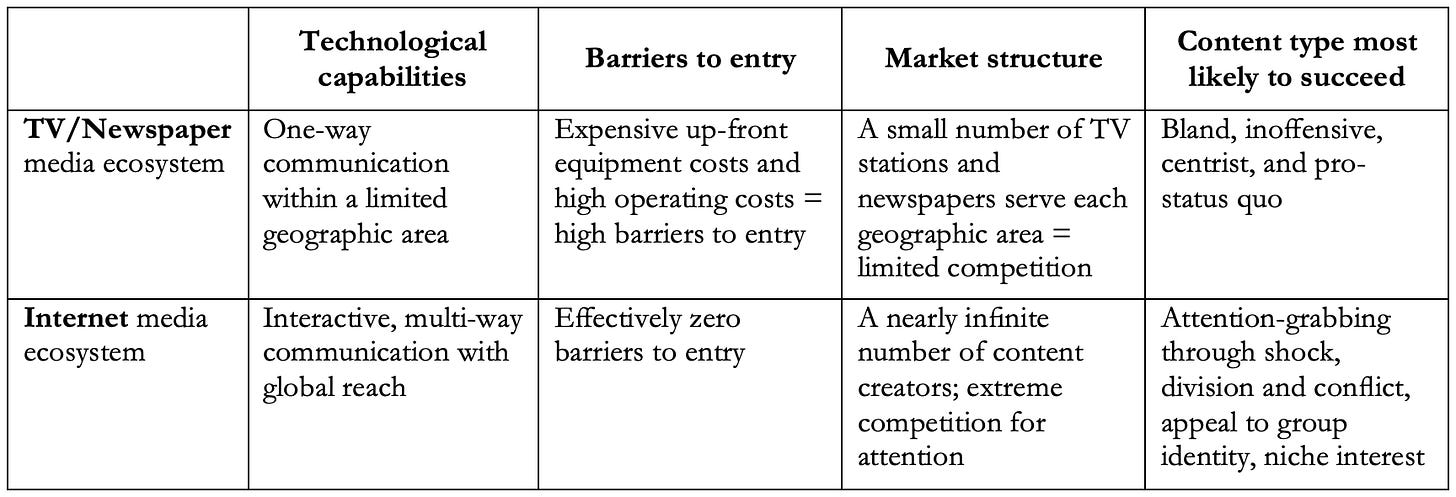

Before the internet, most newspaper content and television programming was bland, safe, and as broadly unobjectionable as possible.1 In stark contrast, today’s modal media content is defined by how it fights for attention by provoking outrage, appealing to factional identity, inciting anger, and employing other divisive tactics.

As we know, this dramatic change was a consequence of the internet. But why and how did it happen? And while it’s obvious in hindsight, why didn’t we anticipate it? The dynamics of the transformation are worth teasing apart because they illustrate a concept that’s highly relevant in our destabilized age.

The 20th century media-information ecosystem was defined by the fact that distributing information was difficult. For example, TV and radio could only "deliver information as far as their broadcast signals would carry, and newspapers only as far as it was economical to send their trucks. These limitations defined the region in which these businesses operated.

In addition to being highly flawed, the leading media-information technologies of the pre-internet era were also extremely expensive. In addition to the pricey machinery and equipment, organizations that produced and distributed media content were expensive to operate because they required scores of people across editorial, production, ad sales, etc. These substantial startup and operating costs created high barriers to entry for the markets in which media companies operated.

Those high barriers to entry meant upstart challengers were rare. As a result, newspapers, TV stations, and other media companies operated in markets with relatively few competitors. This market structure determined the nature of the competition the handful of media companies in each region were trying to win.

Limited competition results in large market shares, which means audiences with a broad range of views, tastes, and preferences. The optimal way to compete in such a market was to provide content that was unobjectionable to most people. The net result was news and entertainment that was centrist, safe, and bland (which, happily for media company owners, aligned nicely with the preferences of advertisers).

—

The rise of the social internet in the early 2000s radically upended the existing media-information ecosystem. As the old one was collapsing, a new and unprecedented system emerged. Instead of a small handful of broadcast nodes, there were millions. And rather than operating within limited geographies, each node had global reach courtesy of the internet.

This shift tore asunder the industry’s once insurmountable barriers to entry. With just an internet-connected computer, suddenly anyone could be a publisher or broadcaster. Just as high barriers to entry structured the previous media-information ecosystem, nearly nonexistent barriers have shaped the current one.

With the barriers to entry gone, every legacy media company went directly from limited competition to competing with every creator-publisher on earth. The attention war had begun. We know this story well at this point, but the scope and speed of this change is hard to completely one’s head around.

While the amount of content online multiplied rapidly, human attention did not. And because commanding attention translates to money, fame, and influence, the competition for it was fierce. Winning this attention war became an essential element of success for every established and aspiring creator-publisher in the world. The result was an explosion of content crafted to grab attention. It turned out what was most effective at seizing attention was triggering people’s lizard brains by inciting anger, appealing to group identity, provoking outrage, and so on. There’s plenty of positive, high quality content out there - indeed, far more than before the internet - but it’s often drowned out by a cacophony of anger and division.

Context Dependence

There’s a lot to say about how the internet sparked the transformation of the media-information ecosystem. Here, I want to focus on a less salient aspect.

In the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, the sort of TV we watched and news we read had been around so long it felt like the natural order of things. But it wasn’t, as we would soon learn. Instead, the content types produced by the pre-internet and internet media ecosystems are context dependent. In other words, the features and output of both ecosystems are emergent phenomena that materialized as they did because of the context - i.e. the core technology, the barriers to entry it creates, how those barriers structure market competition, and the type of content mostly likely to win.

This concept of context dependence is important, but it isn’t new or complicated. It’s essentially a different way of saying, “because complex systems are complex it’s hard to predict how they’ll transform in response to a shift in conditions or other stimulus.” Nevertheless, I like the term context dependent. First, it reminds us that most of what’s around us is contingent on inputs and forces we can’t see and on relationships that we aren’t aware of and don’t understand. Second and more importantly, I like the term because this era is anomolous.

Change is a constant in the world, but change exists on spectrum of scale and disruptiveness. We’re now in a period large scale, highly disruptive change involving the rapid transformation mega-systems - our media ecosystem and our planet’s climate system, just to name two.2 It’s causing ripples in every direction, which manifest as big second order effects like increased climate migration and the rise of authoritarian forces in the U.S. and Europe.

With more large scale shifts likely as the previous era’s equilibrium continues to unravel, we need to invest time and energy to answering big questions like, “What else is going to change as a result of this transformation?” and then to figuring out the concrete actions that will maximize preparedness.

We’ll come back to this idea.

In practice this meant most white people, and especially those comfortable with the status quo. For context, whites represented between 87 and 90 percent of the U.S. population between 1940 to 1970. That percentage declined to 83 percent in 1980, 80 percent in 1990, and 75 percent in 2000 as the effects of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 rippled through American society.

This isn’t a complete list, but in addition to the media-information system and global warming we’re also seeing: population decline in developed countries (increased urbanization —> lower birthrates), a transitioning global energy system, and rising geopolitical tensions among superpowers.

I can't wait to see this article expanded upon!