The world is destabilized

An overview and synthesis of political polarization, a disunity-generating media ecosystem, and the climate crisis

This week’s analysis is a synthesis of everything I’ve written up to now, an effort to summarize what Destabilized is saying.

Two quick things before I start:

Sometime soon I’m going to share a few thoughts on optimism and pessimism as frames for thinking about the future. For now I’ll say my aim is to describe the world as it is, avoiding any slant, optimistic or pessimistic. You’ll be the ultimate judges of how close I come to that ideal.

I’ve spent a lot of time time in the last two days reading up on Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. I plan to write about it in the future. Today I’ll just note that it’s at least partly a symptom of the overall destabilization in the world, and will likely also be an accelerant of it.

Okay, on to this week’s analysis.

Destabilized has analyzed three drivers of instability: highly polarized politics, a divisive media ecosystem, and the climate crisis. Each is distinct, but all three interact in complex and potentially explosive ways.

Highly polarized politics

Politics in the U.S. and elsewhere has become extremely polarized. America’s two major parties have sorted into opposing camps based on ideology and identity – race, religion, education, region, gender, and age. This process was triggered (accelerated, really) when LBJ signed the Civil and Voting Rights Acts into law in the mid-1960s. The parties have been realigning in response ever since, with Democrats growing more liberal (and more racially diverse), and Republicans growing more conservative.

Fast forward this process to today, and 51 percent of Biden voters and 57 percent of Trump voters1 strongly agree with the statement:

I have come to view elected officials from the [other party] as a clear and present danger to American democracy.

I just have to emphasize that more than half of American voters said they “strongly agree” with that statement, even though “somewhat agree” was available as an option had they wanted to express the sentiment in a more moderate way. We should always take public opinion surveys with a large grain of salt, they are flawed tools for assessing the public’s views and state of mind. But even factoring that in, these numbers are bad.

A dangerous aspect of this polarization is that the conflict largely revolves around the foundational question of whether American society will be defined by social and racial equality or by social and racial hierarchy. Whether all Americans are fundamentally equal is a question not just about the relative status of individuals and groups, but also about our society’s degree of commitment to democracy.

These are among the unresolved political and cultural conflicts that have existed since the 17th century. While some aspects of these conflicts, like questions of government regulation of industry, are amenable to compromise, the question of social equality vs. social hierarchy is politically volatile because it goes to the heart of the human dignity of people and groups, which means there is no stable middle ground. To resolve the conflict, one side will ultimately have to win and the other will have to lose.

Divisive media ecosystem

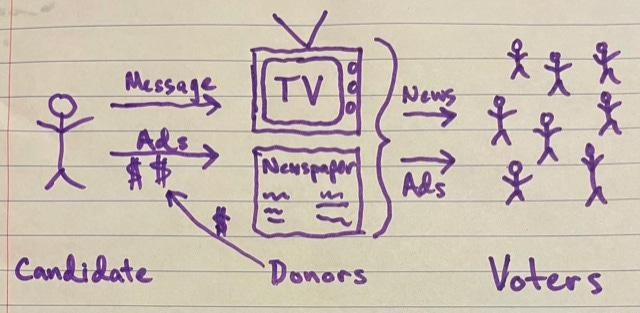

The media ecosystem between 1950 and 2000 was dominated by newspapers and broadcast television. The nature of these information technologies, especially their market dynamics, created strong incentives for safe, broadly appealing content:

In the context of a media market with a small number of competitors (TV or print), the way to maximize the size of your actual audience is to maximize the size of your potential audience. You do this by offering content that’s safe and unobjectionable because it appeals to values and preferences that are widely held. The other station heads and the publishers of the local papers have the same incentives, so every media outlet ends up offering a similar flavor of centrist, unity-inflected stories in the form of news, features, and TV shows.

A lot of safe, broad-appeal news and programming reinforced the ideas of the American story: the country belongs to all of us, we all have a stake, and we’re in this together. Generations of popular TV shows like Happy Days, Family Ties, The Wonder Years, and more, as well as newspapers and local and national TV news programs, delivered a consistent meta-message of decency and unity among good Americans. This was the narrative air we breathed for the 50 years between World War II and the rise of the consumer internet in the mid-1990s.

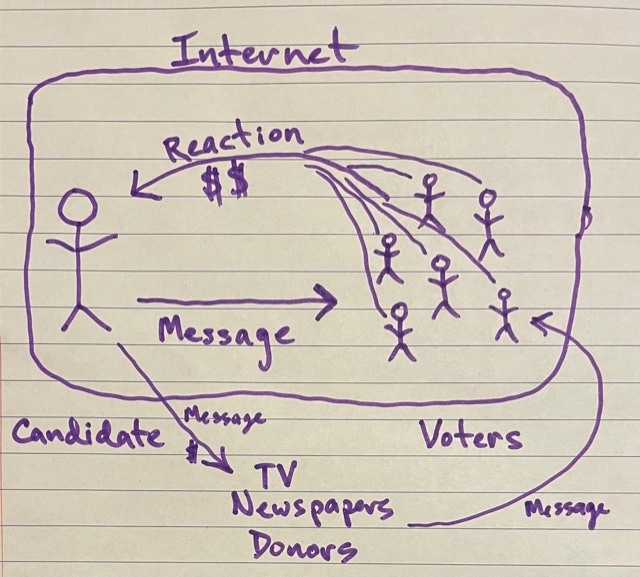

In the postwar media ecosystem, the paths to getting information in front of a large audience all went through media gatekeepers – TV stations, newspapers, movie studios, magazines, and book publishers. In stark contrast, today’s internet media ecosystem enables anyone anywhere with an internet connection to reach hundreds of millions of people.

But there’s a catch: your content will only reach a large audience if it grabs the attention of enough people and motivates them to share it. These incentives create a permanent “attention war” in which people fight to get noticed. This fight, it turns out, is be fought most effectively with certain kinds of divisive content:

Once the attention war began, content creators needed better ways to get noticed. Every piece of content they produced doubled as an experiment in how to grab attention. Across billions of these attention experiments, people learned what styles and flavors of content drew the most engagement. It turned out the best ways to get attention were provoking outrage, appealing to factional identity, instilling fear, and inciting anger and hate. These “activated” or hot emotions moved the most people to like, comment on, and share a piece of content. Heavy engagement with hot-emotion content represented attention war victories, driving more creators to produce content with similar emotional effects. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Research backs up the power of hot emotions to motivate action. NYU professor of psychology Jay Van Bavel and colleagues analyzed more than half a million tweets and found for each word with both moral and emotional resonance – like “shame,” “punish,” and “evil,” but not “fear” (emotional only) or “duty” (moral only) – the number of retweets increased by 20 percent.

We see this dynamic on a daily basis when the most dogmatic or outrageous political and media figures, and those who pick the most fights on behalf of their faction, cause the biggest controversies and, as result, receive the most attention.

Today’s effectively infinite number of information sources require each person to select a subset to pay attention to. Whatever mix of established news outlets, Twitter accounts, subreddits, discord servers, or WhatsApp groups a person chooses, the result is the same. Whereas the newspapers and TV ecosystem forced everyone to consume the same information from the same few sources, the internet media ecosystem results in different subgroups relying on entirely different sets of information sources.

Content providers are incentivized to give their audience what they want because if they get antsy, an alternative is only ever a click away. Therefore, if an audience wants accurate, objective news, it will tend to be well informed. But if, deep down, the audience wants stories about how their side is good and the other side is bad – or, worse, fantastical conspiracy theories about the true nature of the world that elites are trying to keep hidden – then it will tend to have an inaccurate understanding of the world.

This state of affairs is incompatible with functioning democratic processes.

—

A politics that’s highly polarized around identity and ideology, and a media ecosystem that incentivizes conflict-oriented rhetoric, demonizes out-groups, and reinforces in-group identity, is a volatile combination. The two create a self-reinforcing cycle of disunity with no obvious mechanism to disrupt it.

Climate crisis backdrop

The re-alignment of the parties and the disunity-generating internet media ecosystem is more than enough to make this a period of democratic crisis and instability in the U.S. But an even more profound crisis is unfolding at the same time. And the climate crisis is not happening in a separate sphere, it’s intermingled with and exacerbating political turbulence in multiple ways.

The climate crisis causes physical, financial, and emotional hardship every time a climate-intensified storm or fire destroys property and injures and kills people. These events will grow more frequent and destructive over time.

Climate refugees from Central America and elsewhere are arriving in the United States while the right-wing base of the Republican Party is in a state of revolt over the decline of white demographic dominance and cultural power.

Home insurance rates are starting to rise in climate-vulnerable places, which will drive down the value of people’s homes. Fortunately, this isn’t most places, but that doesn’t matter to those whose personal/family wealth gets crushed.

The crisis creates a high-stakes struggle between fossil fuel interests and everyone else – especially the young. The volatility of the struggle could increase in line with the growing urgency of greenhouse gas reductions.

Ever increasing numbers of global climate refugees are seeking safe havens, a dynamic that tends to fuel reactionary political movements and boost autocratic leaders.

Disorder, loss, and economic insecurity tend to breed fear and bring out the worst in people. In the context of polarization and internet media-fueled disunity, it’s a dangerous mix.

Only a little of the above is speculation. Most is either a description of the present or anticipation of highly likely futures (e.g., increases in extreme weather and climate refugees). The rise of reactionary movements and authoritarian leaders isn’t certain – it’s possible we’ll come together and welcome refugees (or keep them out entirely) – but little of we’ve seen on this front in recent years is encouraging.

We haven’t yet discussed several potential sources of instability. These are less certain and harder to extrapolate into the future, but have the potential to contribute to growing instability:

The traumas of the pandemic experience. Loss of loved ones, scary health close-calls, long Covid, extended loss of social contact, and witnessing loved ones and neighbors descend into conspiracy and extremist rhetoric.

Ongoing pandemic stress and uncertainty, including ongoing fights over vaccines and masks and the unpredictability of new variants.

High levels of economic inequality.

The presence in the U.S. of 400 million privately owned firearms.

A looming ground war in Eastern Europe.

The potential for a new Cold War with Russia and China.

Rapid and accelerating technological innovation, including artificial intelligence, the metaverse, and cryptocurrency/web3.2

Again, we don’t know exactly what effects these will have in the years ahead, but they all have the potential to be significantly destabilizing, especially since they will all unfold in the context of the polarization-internet media-climate crisis vortex.

There’s an important caveat in all of this: there has always been, at literally every moment across history, a lot of bad things happening in the world. The challenge is to distinguish between problematic dynamics that will tend to worsen, and those that will likely remain relatively static or improve over time.

It’s also critical to remember we can’t perfectly predict the future. I don’t know exactly how things will unfold over the next year or next decade. But even when we limit our analysis to what’s known and knowable, there’s no question we’re currently in a period of destabilization, and little doubt it will worsen in the coming years.

Going forward I’m going to start interspersing analysis of the kind I’ve been doing thus far with practical advice for living, parenting, investing, and leading organizations in our turbulent era.

I have one request of you, which is important for the long-term health and durability of Destabilized. If you would, please try to think of one or two people who might be interested in the newsletter, or who could benefit practically from it, and share it with them and suggest they subscribe.

Thank you, and thanks for joining me on this journey!

Notes

https://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/new-initiative-explores-deep-persistent-divides-between-biden-and-trump-voters/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estimated_number_of_civilian_guns_per_capita_by_country

An addition 29 percent of Biden voters and 27 percent of Trump voters somewhat agree with the statement, for totals of 80 and 84 percent, respectively.

These technologies may end up having only modest impacts, or they could be transformative. All of them move the world further away from the past MAGA reactionaries seem to want to restore. They will also tend to deepen the significant societal and political divide based on education.