Quick intro: One of the things I want to do with Destabilized is learn in public. Today’s post is in that spirit, with various semi-formed thought fragments and out-loud wonderings. Candidly, it forces me out of my comfort zone somewhat, but I love learning and I always enjoy when other writers share their learning process in public. I hope you will feel similarly about this.

In a post last October I wrote:

It’s not news that Americans are divided between red and blue, but it’s striking how extreme it’s become. In a recent University of Virginia Center for Politics poll, 78 percent of Trump voters and 75 percent of Biden voters said they strongly or somewhat agreed that “Americans who support the [other party] have become a clear and present danger to the American way of life.” All surveys should be taken with a grain of salt, but this finding isn’t an outlier and, regardless, it would take an entire salt mine to make it anything but alarming.

There’s been extensive discussion of the growing hostility in politics, but despite its significance it remains under-explained. Where did it come from?

The source of American political division is in many ways the big question of our time. Today I’m going to offer some historical perspectives and thoughts that I hope include some new lenses and paths for further learning.

Countries are “imagined communities,” in Benedict Anderson’s unforgettable phrase, which means they’re brought into being in large part by stories about the cultural inheritance and sacred symbols citizens share in common. Stories are the mechanism that allow us to collectively imagine ourselves as members of the same national community. In order for a country to be cohesive, therefore, its stories must accentuate citizens’ shared history, values, religion, challenges, and victories in a way that produces feelings of affinity with one another and also pride in being a member of the community.

Ideally national stories are also true. An untrue story has a degree of brittleness that transfers to the country it brings into being. This means even if a subgroup within a country does horrible things to another subgroup, the reality of those events can’t take up too much space in national stories without undercutting the feelings of affinity and pride necessary to hold the country together. A country faces a choice if and when this happens: either teach the truth and risk weakening the bonds of nationhood, or preserve national cohesion by telling a story that elides ugly, divisive truths.

It’s not the only reason, but this national imperative for positive, unifying stories is part of why we learned so little in school about the brutal, degrading racial caste system that defined the American South from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 until the culmination of the civil rights movement in 1965.1 Similarly, though we learned about slavery, it was generally in a way that we never quite absorbed the magnitude of the moral atrocity that was 200 years of sanctioned violence, torture, rape, and other forms of dehumanization. We were taught something we might call “propaganda of omission” – it wasn’t false, but it certainly wasn’t the truth.

I’ve been wondering recently to what extent this propaganda of omission skewed my ability to see my own country with clear eyes. If my foundational mental models of the United States were indeed slanted, what might I see differently if I could free myself from those distortions?

In his 2011 book American Nations, historian-journalist Colin Woodard documents the origins, motivations, and cultures of the eight distinct groups of Europeans who settled what was then called the New World. They were of many classes, came from various countries, with different motivations, religious traditions, and cultural values.

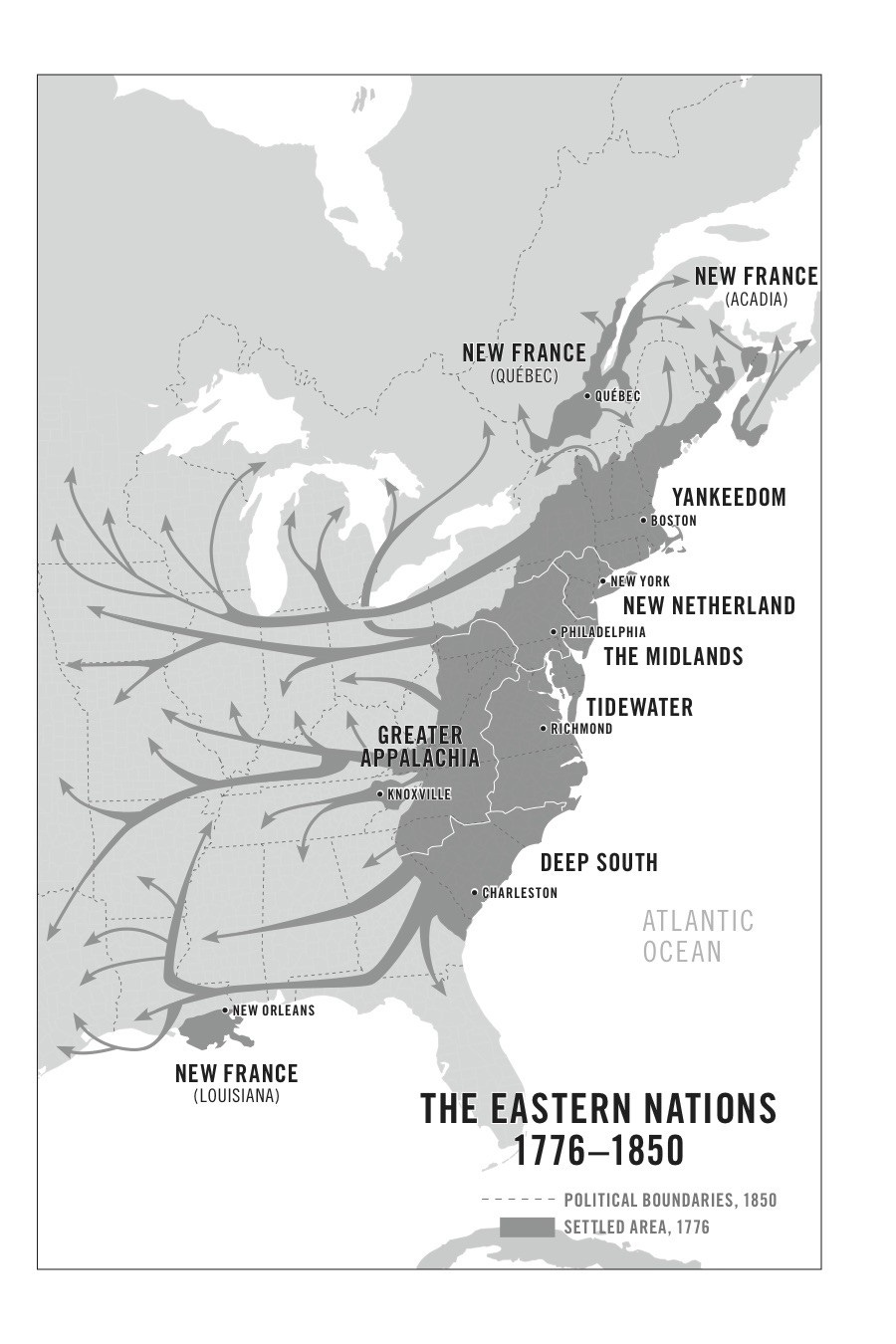

Map of the “American nations”:

Woodard calls these groups of European settlers “nations” – hence the book’s title – arguing that each has the shared history, ethnic background, culture, and sacred symbols that characterize nationhood.2 He argues the divergent values and struggles for power among these “American nations” have fueled U.S. political conflicts throughout our history. (There are eleven nations overall, the eight below plus the Left Coast and Far West, which were largely settled by members of the original eight, and First Nation, the Indigenous peoples of North America.)

Here’s an extremely brief overview of the eight initial American nations that came from Europe. I encourage you, if you’re so inclined, to look at the above map as you go (or, even better, read the book).

El Norte was established in the late 1500s by Spanish empire missionaries and soldiers, who arrived in modern day U.S. territory through Mexico. It might have ended up having significant cultural influence on a larger area had its system of religious conversion not been so corrupt, abusive, and violent, and thus unappealing to potential converts.

New France was settled by veterans of France’s Reformation wars who wished to avoid such atrocities in the future. They sought to establish a tolerant, peaceful feudal society that would live in harmony alongside Native Americans. They arrived in Acadia in what is now Maine, later migrating to modern day Quebec. One of New France’s initial leaders, Samuel de Champlain, wanted, like other European settlers, to bring a version of his French civilization to the Native Americans. But he had the radical idea that this should be done by example and persuasion while living as neighbors with the Indigenous populations. The New French treated Native Americans as equals, and the societies intermingled over time.

Tidewater was the first English colony in North America, initially established by an investor-funded expedition. Tidewater eventually overcame a range of struggles, including a years-long brutal war against Indians led by Chief Powhatan, and transformed into a plantation society when the English settlers discovered they could grow and export tobacco. Tobacco was labor intensive and grew best in virgin soil, which created imperatives for territorial expansion and a growing supply of labor. Tidewater initially recruited indentured servants from London, Liverpool, and elsewhere, but it was insufficient. Later, they followed the example of Barbadian and Deep South slavers and bought enslaved people to do the grinding work. Tidewater was a society dominated in all ways by a small group of rich and powerful plantation owners. Laborers had no political rights and slaves were treated as property.

Yankeedom was settled by an idealistic English group, the Puritans, that believed they were God’s chosen people. The Puritans were highly educated and rejected inherited privilege. They wanted to create a utopian Calvinist society, which meant prioritizing the greater good of the community over individual prerogatives, enforcing strict religious morality, and rejecting or aggressively assimilating outsiders. They believed strongly in the power of government, especially local governments, to make better societies. The elites of Puritan Yankeedom were distinguished by education, not defined not by nobility of birth.

New Netherland, the area that today is greater New York City, was founded by Dutch settlers in 1624 as a fur trading post governed by the Dutch West India Company. The Dutch culture of tolerance facilitated a wide range of trade, and allowed the area to grow strikingly diverse. The diversity was tolerated, not celebrated, and ethnic and religious groups jockeyed for business and influence. New Netherland was a stronghold of loyalists during the American Revolution, attracting many who sided with the British. When news arrived in 1783 that the colonies would have full independence from the crown, as much as half of the population escaped the area, seeking safety in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Britain itself.

Greater Appalachia was settled starting in the early 1700s by Scots-Irish veterans of brutal wars in Scotland, Ireland, and northern England. The region has a deep-seated belief in personal liberty and a distrust of outsider authorities. The region, one of the largest geographically, extends from south-central Pennsylvania into West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, parts of Arkansas and Missouri, eastern Oklahoma, and most of Texas. People in Greater Appalachia today are more likely than Americans in any other part of the country to respond with “American” when census takers ask about their ancestry.

The Deep South was founded by descendants of the English settlers of Barbados. Their fathers and grandfathers had turned Barbados into a brutal slave colony that even at the time was known for its extreme cruelty. When they ran out of land, the second sons of Barbadian planters (who wouldn’t inherit the family business) sought new territory on which to create their own sugar plantations. When they found it, they developed an equally savage replica of the Barbadian plantation system. Substantially outnumbered by the people they enslaved, plantation owners of the Deep South feared slave uprisings, and responded by militarizing the society. Enslaved people developed their own distinct culture, music, and foods, drawing from the influences of their varied nations of origin.

The Midlands was founded by a group of English Quakers, who were the most controversial religious group of their time. First established in Pennsylvania, its Quaker founder William Penn dreamed of a society where people of different beliefs and backgrounds could live together in harmony. This extended to an aversion to slavery, and Pennsylvanians were early vocal opponents of the institution. A wave of early immigrants from Germany included religious minorities like the Amish and the Mennonites, seeking freedom of worship. Quaker pacifism and belief in the inherent goodness of people led to ineffective governance and challenges when faced with violent threats, which ultimately ended the Quaker dominance of political affairs in the Midlands.

After initially settling in one area, each national group migrated to other regions over time, bringing their culture with them. These migrations resulted in fights over control of the Left Coast and Far West as the population headed west in the 1800s.

The very different European groups that settled in the New World wound up together, their fates intertwined without meaning to. They were largely separate at first, coming together to coordinate actions only as the increasingly powerful British Empire sought to subjugate, rule, and tax the colonies. Because each nation cared about itself first and foremost, and had starkly different values, priorities, and interests from the others, many wanted no part of a resistance effort. The nations didn’t trust one another – many feared the rebellion against the British was a Yankee ruse to gain control of all of North America. Coordination was challenging to say the least.

John Adams later wrote of the colonies leaders’ efforts to coordinate their rebellion:

…intercourse had been so rare and their knowledge of each other so imperfect that to unite them in the same principles and the same system of action was certainly a very difficult enterprise.

After the American Revolution was over and the British defeated, the incentives to coordinate in order to resist stronger rival nations were less urgent but just as strong. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania worried in 1776 that if New England (Yankeedom) broke away from the other colonies it would lead to

centuries of mutual jealousies, hatreds, wars, and devastations, until at last the exhausted provinces shall sink into slavery under the yoke of some fortunate conquerer… Disunion among ourselves [is] the greatest danger we have.

We know the history from here. They tried the Articles of Confederation, which gave the central federal government too little power and soon failed. Then they wrote and ratified the Constitution, which reflected in many of its particulars the the uneasiness of the coming together of the 13 original colonies (eight American nations). The Constitution has now endured for more than two centuries, during which time the United States of America became the most powerful country in the world, even as the ideological and values conflicts among its original European settlers remain, to a surprisingly large extent, at the heart of our politics.

Here’s a question: does the United States have the qualities nations need to be cohesive in the long run? In some ways, 246 years since the Declaration of Independence, it has a shared history, though that history is often shared only by some, not all. Do we have a shared culture? In some superficial ways yes – many Americans watch the Super Bowl, celebrate Christmas, and have cookouts on the Fourth of July. But in important ways, no, and the diverse origins and worldviews of the eleven American nations is a key underlying reason why.

Perhaps most importantly, does the U.S. have a story that accentuates the shared cultural and political inheritance of its people? And if so, how does the story handle the moral abomination of slavery and the subsequent subjugation of Black Americans in the Jim Crow South? What national narrative could mend those wounds, and what are the implications if one can’t?

As often happens, as I was writing I kept realizing there was a LOT more here than could fit in one post, so I’ll continue this line of inquiry in the weeks to come.

Thinking about America’s national stories, I’m left with two questions in particular:

Given the clashing cultural values of America’s European forebears, as well as the deep conflict over slavery that led to the Civil War and killed 750,000 people, how was America able to remain a relatively cohesive country for so many decades extending across the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries?

What has changed from 50, 25, or even 10 years ago, when America was reasonably stable, to now, when the country is extremely divided and politically unstable? In other words, how did we remain a fairly cohesive country then, and why isn’t it working now?

I’m excited to keep learning with you!

Notes

https://colinwoodard.com/books/american-nations/

Another is the curious efforts of some historians to whitewash the oppressive, violent nature of the Jim Crow South.

As you may already know (but a refresher never hurts), nations and states are different things. A nation is a group of people who comprise a cohesive unit and share, or believe they share, a common history, culture, language, and symbols. A state is simply a sovereign political entity recognized by other countries as a country and eligible for UN membership. A nation-state is a state that consists entirely or mostly of one nation (though the term nation-state is often used imprecisely). There are a quite a few nation-states (e.g., Egypt, France, Japan); many nations that don’t have their own state (e.g., the Kurds, the Québécois, the Uyghur people); and plenty of states that contain more than one nation (e.g., India, Canada, Brazil, and… the United States).