In its two years of existence, Destabilized has focused on three dynamics disrupting our world: climate change, the internet, and rising authoritarianism. The three topics, it’s worth noting, aren’t conceptually equivalent. The first two are mega-scale complex adaptive systems that have been destabilized, causing a wide array of ripple effects and consequences. In contrast, authoritarianism is itself a consequence of these and other forces in the world.1

Today I’m adding a new, fourth, destabilization dynamic: low birthrates and population decline. This is a generations-long trend that in much of the world has already fallen below the critical level required for population maintenance. On its own, its impact isn’t quite as profound as the first three dynamics (an extremely high bar). But it’s both significant in its own right and interacts with other destabilizing forces in complex and potentially dangerous ways.

—

Before we start, I want to offer a very important caveat.2 The demographic implications of declining birth rates are, in a sense, the factual basis of the “great replacement theory,” a hateful white supremacist conspiracy theory that claims Jews are masterminding the immigration of black and brown people to the United States and other western countries in order to dilute/replace the current white majorities. Like all antisemitism, this idea is false, dangerous, and bigoted. The great replacement theory is also shot-through with hate toward African-Americans, Hispanics, Muslims, and others. Proponents of the theory are exactly who you’d expect. The mass murderer who killed 51 people at a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand titled his online manifesto “The Great Replacement,” and the perpetrators of other mass shootings - including in Pittsburgh at the Tree of Life synagogue, El Paso, and Buffalo - have echoed the same odious themes. When torch-bearing white supremacists chanted “The Jews will not replace us!” in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, this is what they meant. The great replacement theory has also been advanced, subtly and not, by scores of American and European elected officials and media personalities on the far right.

Needless to say, I find the great replacement theory utterly abhorrent and nothing in this analysis aligns with or supports it.

Despite deranged bigots spinning it into a vile conspiracy theory, falling birthrates and their potential implications are important and worthy of discussion. The population of a country changes based on the balance of:

Births

Deaths

Net immigration (the difference between people arriving and people leaving)

If there are more births than deaths, the population tends to grow; if there are more deaths than births, the population tends to shrink (obviously!). The overall increase or decrease of a population depends on the balance of these three factors.

Assuming stable mortality and net zero immigration, countries need to average 2.1 births per woman to maintain a steady population.3 (Talking about women in terms of their number of offspring often feels, to me, reductive and demeaning, yet the data on fertility rates is key to understanding population changes.)

In the first decades of the 21st century, most developed countries and some developing ones have fallen below this level. (There are debates over why. Key drivers include birth control, women’s rights, and urbanization - kids were economic assets on the farm, economic liabilities in the city.)

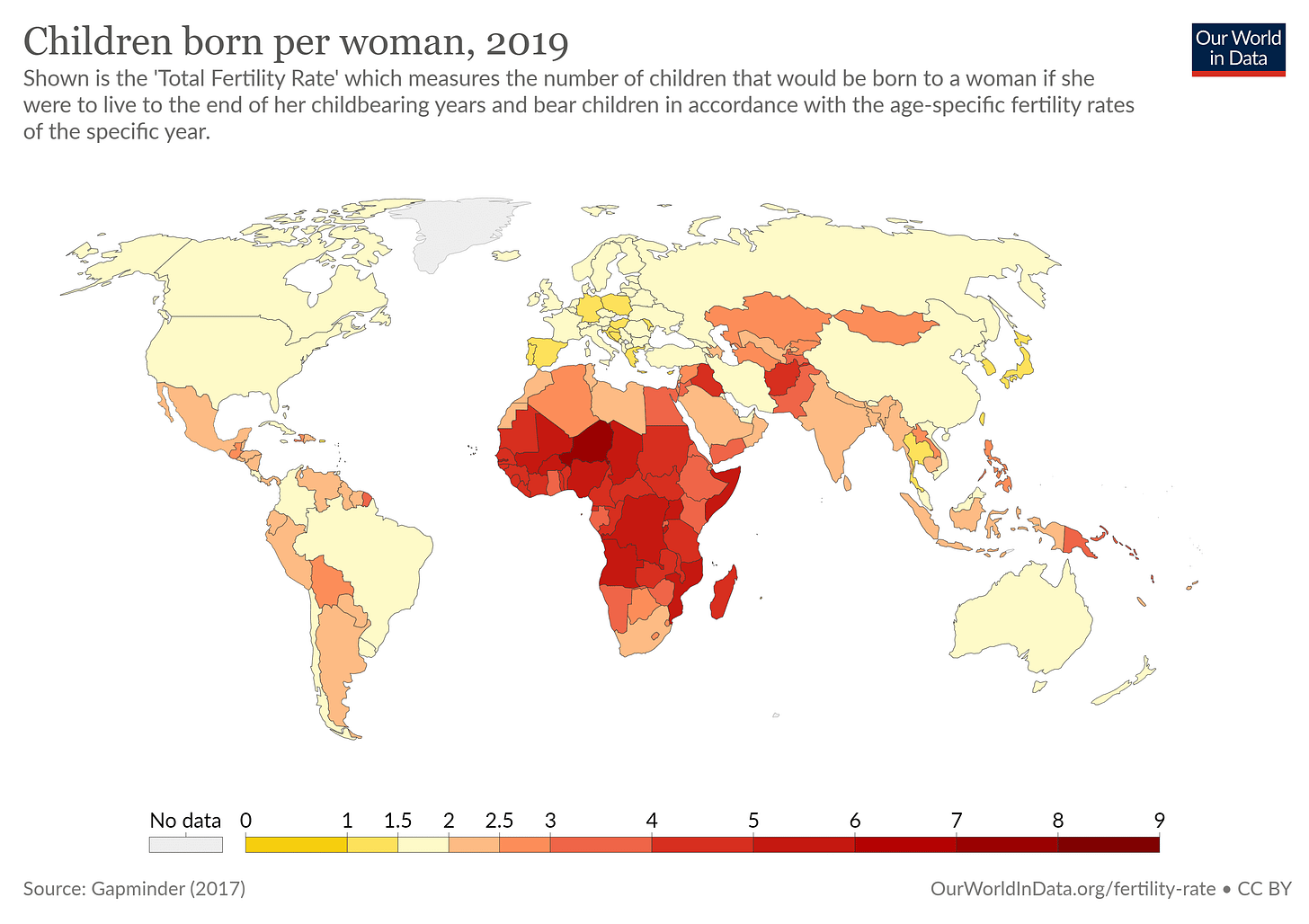

If the countries in yellow on the map above stay below 2.1 births per woman, they will eventually reach the point where deaths exceed births.

A small group of countries are already there, including Japan, Russia, Spain, Italy, and several in Eastern and southern Europe (yellow in the map below). The populations of these nations are either already declining, or they’re maintaining positive growth through immigration.

Immigration can boost a population, but if a country becomes less appealing to immigrants and inflows slow, their population will start to shrink. Separately, ongoing substantial levels of immigration can lead to other challenges.

That brings us to the core of the issue: when birthrates fall below population replacement level, countries face difficult choices. In a recent paper called Migration, Stagnation, or Procreation: Quantifying the Demographic Trilemma, two right-leaning British social scientists analyzed the options and tradeoffs.4 They describe a “trilemma” in which countries can have any two, but not all three, of the following:

Low birth rates

Economic vitality

Low levels of immigration and thus “ethnic continuity”

Many, including me, disagree strongly that “ethnic continuity” should be a goal, and I find even the phrase disturbing. But there are many places where rapid changes in ethnic makeup have caused friction and, in some cases, triggered political backlash.

The rise of Donald Trump had multiple causes, but it was fueled in large part by the resonance of his attacks on immigration (the U.S. went from 88 percent white in 1970 to 62 percent white in 2020).

Brexit was an expression of white English nationalism generally, and anti-immigrant sentiment specifically (between 2001 and 2021, England and Wales together went from being 88 percent “white British” to 74 percent).

The ongoing rise of far-right parties across Europe has many factors, one of which is growing opposition to the levels of immigration in recent years.

Even while pushing back against the conflict entrepreneurs who blame life’s frustrations on immigrants, democratic governments seeking to maintain domestic tranquility countries may opt to limit immigration to a low or moderate level.

And yet the math and logic of the trilemma tells us it’s not so simple.

—

But wait, before we go further, why aren’t death rates part of the trilemma? The short answer is because death rates are hard to change in the short- and medium-term.

Population pyramids show the number of people in each age group in a country.5 Younger societies have bottom-heavy pyramids and therefore fewer deaths per 1,000 residents per year (e.g., Switzerland in 1900, below). Aging societies have top-heavy pyramids and more deaths per 1,000 people per year (e.g., Switzerland in 2100). Whatever the shape of the age pyramid, current death rates were determined decades earlier when today’s older people were born. Death rates are typically changeable only on the margins, and only over the long-term.

Okay, back to the choices available to countries with falling birth rates.

Another way to frame the low birthrate “trilemma” is that a country can either raise birthrates back above 2.1 children per woman, or choose between these two options:

Zero/Low level of immigration —> Shrinking and aging population means a sluggish-or-worse economy; the country’s ethnic makeup is stable.

High level of immigration —> Stable population and age distribution means a better economy; the country’s ethnic makeup transforms more rapidly.

If a country can achieve higher birthrates by making it practically and financially easier to have kids, that may be the simplest approach. There’s just one problem: many have tried, investing huge sums of money over many years, and it has proven to be extremely difficult. Australia is one country that attempted to increase birthrates:

Two decades ago, Australia tried a “baby bonus” program that paid the equivalent of nearly 6,000 U.S. dollars a child at its peak. At the time the campaign started in 2004, the country’s fertility rate was around 1.8 children per woman… By 2008, the rate had risen to a high of around 2, but by 2020, six years after the program had ended, it was at 1.6 — lower than when the cash payments were first introduced.

Sweden tried, as well, and also saw mixed and hard-to-sustain results. Sweden’s big upturn around 1990, which was followed by a deep dip, was later determined to have been a “pull forward” of births in response to a “speed premium” that gave parents money if they had a certain number of kids within a particular timeframe.

Hungary may have invested more than any other country in trying to raise its low birthrates, committing 5 percent of its GDP toward achieving the goal. Nevertheless, the EU black sheep has only managed to increase its birthrate from 1.2 to 1.6 children per woman, well short of population replacement level.

Though significantly and sustainably increasing fertility has been nearly impossible to-date, this could conceivably change through some combination of increased incentives, changing circumstances, and time. But it would be a triumph of hope over experience to expect that to happen anytime soon.

Since raising birthrates appears to be a nonstarter for now, low-birthrate countries face the choice we identified earlier:

Zero/Low level of immigration —> Shrinking and aging population means a sluggish-or-worse economy; the country’s ethnic makeup is stable.

High level of immigration —> Stable population and age distribution means a better economy; the country’s ethnic makeup transforms more rapidly.

Since these are likely the only viable options, we’ll dig into each.

—

But first, let’s set the stage by examining how population changes can play out quantitatively depending on countries’ immigration policies.

If a hypothetical country, let’s call it Demographicsland, has a birthrate of 15 people (babies) per 1,000 residents per year, and a death rate of 20 people per 1,000 residents per year, the population will shrink - absent immigration - by 5 people per 1,000 residents per year.

If Demographicsland has 10 million residents total, its population will shrink by 5 * 10,000 = 50,000 people per year (10,000 because a population of 10 million contains 10,000 units of 1,000 people).

[Zero/Low Immigration] This is a net loss of 50,000 people every year. Over a decade, that’s a total loss of 500,000 people, which would shrink the country’s population from 10,000,000 to 9,500,000, a substantial 5 percent population loss. (This, by the way, is about how fast Japan’s population is currently declining.)

[Higher, but still Low Immigration] If Demographicsland allows 25,000 people to immigrate annually, its rate of population decline would be cut in half. In this scenario, its population would fall to 9,750,000 in one decade, and its foreign-born population would increase by 250,000, or about 2.5 percent.

[High Immigration] If Demographicsland decides its economy will perform best in a slow growth scenario and therefore allows 60,000 people to immigrate annually (offsetting and then some the domestic population decrease of 50,000), in 10 years it would grow by 100,000 people, or 1 percent. In this scenario the foreign born share of its population would increase by roughly 6 percent per decade.

If the differential between Demographicsland’s birthrates and death rates stayed roughly the same, the domestic population loss and associated need for immigrants would continue into the future.

Scenario 1: Zero/Low level of immigration

Low birth rates and potential population decline are a big, unprecedented change.6 We have little to no experience with it and we don’t know what to expect. Some have argued population decline could be a net positive, citing potential benefits like:

Fewer workers leads to higher wages and less economic inequality

Reduced demand for housing makes homes more affordable

Less pressure on the climate/environment

The last one may be true eventually, but on a timeline far too long to help mitigate global warming in the next 30 years, which is when it really matters. The other two may or may not come to pass, depending on the rate of automation and immigration, the pace at which housing is maintained and built, and other factors. But even if wages rise and home prices fall, there’s no guarantee the net effect of low birthrates will be positive. That’s partly because a flat or declining population is also an aging one, which may mean:

Less business investment and potential economic stagnation

Fewer workers per retiree, which endangers the financial foundation of safety nets for older residents (Social Security and Medicare in the U.S.)

A dearth of workers to care for the large population of senior citizens

A hypothetical argument is one thing, but how do these pros and cons play out in real life? Japan is the country furthest along in the low birthrate—>declining population process, and so far it’s doing reasonably well. Because of that, people often use it as evidence that we don’t need to worry about population decline:

John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division at the United Nations, said that after decades of exponential growth in which the world’s population doubled to more than seven billion between 1970 to 2014, the doom-and-gloom assessments about declining fertility rates and depopulation tend to be overstated. Japan has been battling population decline since the 1970s, he noted, but it remains one of the world’s largest economies. “It has not been the disaster that people imagined,” Mr. Wilmoth said. “Japan is not in a death spiral.”

It is true Japan is faring alright thus far. But for a number of reasons we should be judicious in extrapolating from Japan’s early experience.

Japan is one of the richest nations in the world and has the economic strength to, among other things, generate economic activity and wealth by having foreign workers produce Japanese goods in overseas factories (e.g., Toyota, Honda, plants in the U.S.). This won’t be true for most countries.

Though Japan’s population is falling, global population - and economic demand - are still growing. Once global demand starts to fall on top of domestic demand, the dynamics may change.

Japan’s typically understated prime minister, Fumio Kishida, said in early 2023 about the country’s low birthrate: “Japan is on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society.” If Japan’s prime minister isn’t confident his country’s preliminary success proves things will be fine, we shouldn’t be, either.

The biggest risks to a country with a declining and aging population is arguably psychological. These countries risk developing, for lack of a better term, bad vibes. Some of this is aesthetic, some is simple ageism. Older countries will certainly have differences with younger ones - people may work longer and stay productive for more of their lives, for example. There are multiple ways to organize a society, and therefore room to adapt and do things differently to account for demographic changes.

Still, an aging society is more likely to have certain qualities. Some of these will be positive, like greater wisdom. Some will be negative, like less energy. Wisdom is certainly invaluable, but when it comes to economic vitality, energy and the activity it produces are essential. If you don’t care for the modern slang “vibes”, consider this from leading 20th century economist John Maynard Keynes:

[A] large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits – of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.

Healthy economies depend on animal spirits, which are mysterious and hard to manufacture or even predict. They are not the sole domain of the young, but they correlate with youth. They also correlate with expectations of a better future, which depends on many factors, one of which may be a large share of young people brimming with potential.

The biggest danger to shrinking societies is that persistently lackluster animal spirits will eventually lead talented young people to seek opportunity elsewhere. This kind of brain-drain can become a downward spiral in which young people leaving worsens economic conditions, which causes more young people to leave, and so on. In addition to being damaging and painful, this dynamic may be hard to reverse.

—

Scenario 2: High level of immigration

Those who believe “ethnic continuity” is important for a nation will not like the impact over time of immigration that’s sufficiently high to keep population steady. In the example above, Demographicsland’s 10 million people had a net loss of 5 people per 1,000 (five more deaths than births), or 50,000 people total per year. If that country wanted some level of growth to avoid the brain-drain downward spiral scenario, it would need to welcome around 60,000 immigrants annually to achieve 0.1 percent annual population growth. If we assume the gap between births and deaths remains steady, then the immigrant share of the population would grow by six percentage points each decade (60,000 per year times 10 years = 600,000, which is slightly less than six percent of 10.1 million). Over 30 years, the country’s foreign-born population would increase by nearly 18 percentage points, a substantial shift.

Sustained high levels of immigration into a country often produce meaningful changes. The United States has changed a lot between 1980, when Americans were 80 percent non-Hispanic white, through 2020 when Americans were 58 percent non-Hispanic white. While I and many others view this evolution and its socio-cultural implications as healthy and revitalizing, not everyone agrees.

Some socio-cultural changes that have accompanied recent demographic shifts are fairly significant, including the normalization of interracial relationships and the relative fluency of young people in socializing across difference among their peers.

Other changes are minor in isolation. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t deeply felt. These include:

A more diverse cadre of movie stars

The now ubiquitous “para Español, oprima numero dos” message on automated voice systems

“Happy holidays” becoming December’s most common greeting

The proliferation of once-exotic cuisines

As a result of these and countless other small changes, full cultural literacy in the United States today takes more knowledge than it used to. We need to know about other countries, other languages, and other religions. There are fewer safe assumptions we can make when we meet new people. These shifts require people to be aware of and think about a category of things they previously didn’t have to. It wasn’t like this in the 1950s through 1980s and, to some, the changes are for the worse.

Whether because of these changes or in spite of them, most Americans still support immigration. But that isn’t the only important question. When we consider societal risks we need to remember that a disaffected group doesn’t need to be a majority, or anywhere close, to sow unrest. Though it’s been claimed by progressives, the famous Margaret Mead quote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has” applies to reactionaries, too.

As I noted above, this is far from theoretical. Europe and the United States have seen elevated levels of immigration in the 21st century while anti-immigrant rightist parties and politicians have steadily gained power on both sides of the Atlantic.

Countries where deaths exceed births (or will soon) are already facing the question about the best path forward. Fortunately for them, demographic change moves slowly.

Unfortunately, though, future demographic transformations are already contributing to societal turbulence. We don’t need to look any further than the caveat I opened with. Violent white supremacists are losing their twisted minds over growing ethnic diversity in majority white countries, and a smaller group of evil lunatics have framed their mass murders as a response to it.

There’s even evidence that Russia’s low birthrate and nascent population decline was a factor in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Between October 2020 and September 2021, the population of Russia experienced its largest peacetime decline since records began, shrinking by 997,000 people.

That would be bad news for any government, but for Putin, it is a disaster. In 2019, he admitted that the thought of a shrinking population “haunts” him. As a result, his haunted regime is now looking for shortcuts to population increases — the targets are Russian women and Ukrainian children.

The link between Putin’s current and potential wars and looming restrictions on abortion is far from subtle. Russian billboards feature the photo of a fetus on one side and the picture of a small boy in a military uniform on the right, with the text stating, “Defend me today, so I may defend you tomorrow.”

Birthrates can and do fluctuate and long-term demographic projections have a somewhat spotty history, but lower birthrates appear to be driven by larger secular trends like gender equality and urbanization, which may make them durable. More importantly for the near-term, low birthrates have already demonstrated their potential to destabilize societies, and for that reason alone need to be taken seriously.

I’ve analyzed authoritarianism even though it’s not a system per se for the simple reason that political systems and governments have an outsize impact on our world and our lives.

Two other points: 1. I believe choosing not to have kids is as good and valid a life choice as any other; and 2. Low birthrates present new challenges, but that doesn’t make them all bad. In fact, two of the big reasons for falling birthrates are reduced child mortality (very good) and women having more options in life (also very good).

The 2.1 children population replacement rate is 2.0 to replace both parents and 0.1 to account for cases where a child doesn’t live long enough to have their own children.

You likely know what a trilemma is, in substance if not by name. It’s a situation where there are three outcomes you want, but you can only have two. The authors offer this, from Slovenian thinker Slavoj Žižekof, as one of the classic examples:

Living in a Communist country, you could be any two, but not all three, of honest, loyal, and intelligent. If you were honestly loyal to the regime, you were not intelligent (you might call it the “dense option”). If you were honest and intelligent, you could not be loyal (the “dissident option”). If you were loyal and intelligent, you could not be honest (the “dissembler option”). By being dense, a dissident, or a dissembler, you were choosing two and foregoing one of the virtues of honesty, intelligence, and loyalty.

Men/boys are on one side of the population pyramid and women/girls on the other because mismatches are important to spot, but the shapes are close to symmetrical.

The thumbnail history of population change in human societies looks like this:

For most of human history there were high birth rates and high death rates. The average woman had many children, the average lifespan was short, and populations grew slowly through brute reproductive force. This was the case for tens of thousands of years.

With the advent of science, medicine, and mechanized power, lifespans extended and death rates declined.

Birthrates also declined due to women’s rights, birth control, and urbanization (children who had been economic assets on the farm became liabilities in the city).

The decline in death rates and birthrates - the first “demographic transition” - led to a disproportionately large working age population, which, for a while, fueled economic growth and vitality. This occurred at different times in different places, but much of it happened in the 20th century.

Many countries are now entering the second demographic transition, in which birthrates fall below population replacement level so that without immigration populations begin to shrink.

The common-sense argument for economic stability requiring population growth requires a much more welcoming immigration policy in the U.S. Unfortunately, due to the Murdoch-enabled toxic sludge that dominates the Republican party, that probably won't happen in our lifetimes.