Climate risk is (still) not priced in

Today's home values do not reflect the climate risk reassessment to come

When I started writing about climate impacts and adaptation in early 2022, I didn’t realize how much time I would spend thinking about homes, real estate vulnerability, and insurance. But, in retrospect, it was inevitable.

It was inevitable first because the effects of climate change manifest in the physical world and therefore increase the risk to physical things, including buildings and infrastructure. Second, it was inevitable because our private and public financial investments in those physical assets are secured with insurance and since insurance costs are a function of risk, as climate risks rise so will premiums (and as premiums rise, home values will fall). And third because lots of people own homes - 65.9 percent of Americans as of 2022 - and have (or should have) insurance, which makes these concerns relevant to hundreds of millions of Americans, and billions of people worldwide.

In recent years, we’ve seen the intensification of climate-fueled extreme weather events, including heat waves, hurricanes, wildfires, droughts, floods, and more.

Climate change is causing heat waves to increase in frequency, duration, season length, and intensity. Deadly and damaging severe heat waves have hit Europe, Asia, North America and elsewhere in just the last few years.

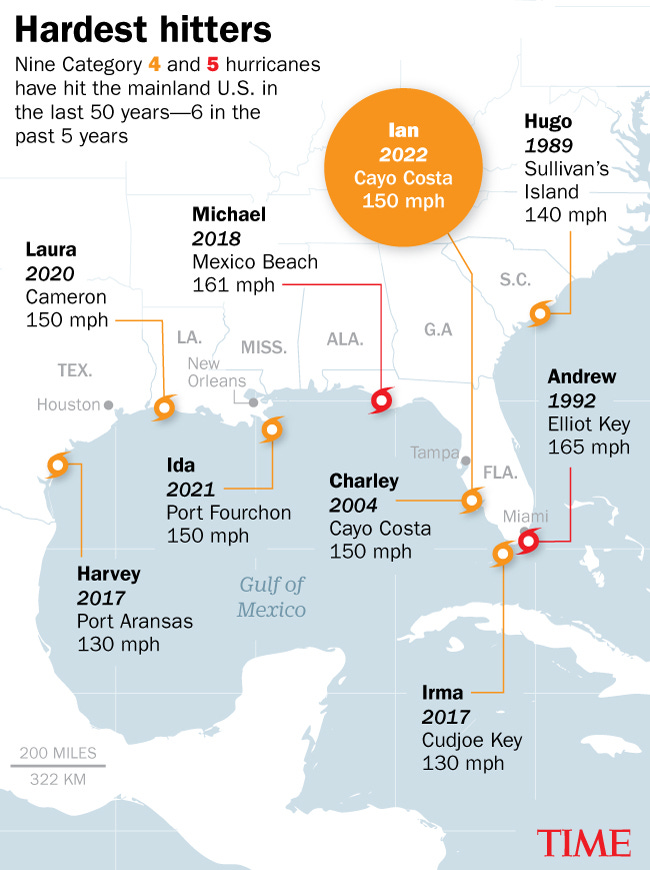

In the last 50 years, nine category 4 or 5 hurricanes have hit the mainland United States. Six of those nine hurricanes have made landfall just since 2017: Harvey, Irma, Michael, Laura, Ida, and Ian (Hurricane Katrina was a category 5 at one point over the Gulf, but arrived as a high-end category 3 hurricane). That means between 1972 and 2016, the U.S. was hit by category 4 or 5 hurricanes less than once per decade (3 in 44 years), while since 2017 we’ve been hit an average of once per year (6 in 6 years).

Many of the largest ever wildfires in the United States have occurred in recent years in California, and six of the state’s seven largest fires have occurred since 2020. This chart of the largest wildfires in California history through 2021 scaled by acres burned offers a visual representation of how fires have grown.

Recent satellite-based research published in the journal Nature Water in March 2023 shows higher temperatures are making both flooding and droughts more extreme. The current mega-drought in the southwestern U.S., the worst in the region in more than 1,200 years, recently led Arizona to enact historic restrictions on housing development due to concerns about long-term availability of groundwater.

We know climate change is already fueling more extreme weather events that are endangering human lives, straining human systems, and destroying homes. The piece that’s harder to keep firmly and clearly in mind is that this trend is only getting started. The natural world is going to grow increasingly threatening and erratic as the earth continues to heat up, which will continue at least as long as we keep pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

As hurricanes, wildfires, flooding, and heat waves grow more intense, the damage they inflict on homes and other property will also increase. And as this trend presses relentlessly forward in the coming years, it will drive a profound change that manifests in two opposite but tightly-linked ways:

The value of homes in climate vulnerable places will fall.

The value of homes in climate durable places will rise.

Change #1 is straightforward: as weather disasters cause escalating property damage in the most climate vulnerable regions, higher insurance premiums and declining market demand will cause the value of homes in those places to fall. Then, as the physical risks, rising insurance costs, and consequent home value declines become salient, people in vulnerable communities will start to leave. Next, the tax bases in these communities will erode, which will increase their borrowing costs, reduce their ability to ruggedize, undermine basic service delivery, and generally making them less appealing places to live. This will accelerate the exodus, further reduce home values, and knock many climate vulnerable areas into long-term downward spirals.

Change #2 is a notch more subtle, but still fairly simple. We know as climate vulnerable places become less appealing due to mounting climate damage, falling property values, and declining quality of life, climate-aware people with the financial capacity and life flexibility to move will start leaving. Where will they go? The topline answer is they’ll seek out appealing places to live that are more climate durable than the places they’re leaving. In the process, the value of homes and other property in these more climate resilient places will increase, benefitting the people who already live there.1

The economic logic is simple: when demand for homes in climate durable places increases, the imbalance of supply and demand will tend to increase both prices and supply (see graph). But because the supply of homes can only increase a little in the short-term, prices will increase even more.

(This gradually sloping supply curve reflects a hypothetical housing market, probably somewhere in the Sun Belt, that has lots of land use/zoning flexibility to build new units in response to higher demand. In more heavily regulated markets like Boston, greater New York City, much of California, and exclusionary suburbs everywhere, the supply curve would be steeper, reflecting the reality that the quantity of homes available can only grow incrementally in response to higher demand, while prices can increase a lot faster and a lot more.2)

The combination of these interconnected shifts - declines in home values for some and increases in home values for others - will result in a shift in wealth away from residents of climate vulnerable places to those in climate durable ones. This climate wealth shift will become a mega-trend in the years ahead.

The climate wealth shift will obviously have profound effects at the family level, as some families grow more financially secure while others are left financially precarious. It will also have a significant impact at the societal level. Most people’s home is their largest financial asset and when it declines in value it will leave many financially ruined. The precise societal impacts are hard to predict, but there’s little doubt this dynamic will be a source of instability. The question is of what magnitude. Regardless, there’s a strong argument for policies that can cushion this coming blow.

The climate wealth shift will be a mega-trend and therefore you might reasonably assume lots of people are thinking about how to get on the right side of it. You might then think that if enough people are thinking about it, maybe it’s already begun and is perhaps even well underway. But a couple weeks ago I saw something that suggests it isn’t. Sean Sweeney, a Minneapolis-based real estate developer who’s smart, successful, and highly regarded on real estate Twitter (“retwit”), tweeted this:

[Internet norms and culture being what it is, I want to say explicitly that I respect Sean’s willingness to admit genuine surprise about something in an effort to learn more about it. It’s a marker of intellectual integrity. Nothing I write here is meant to “dunk on” him. Also, for real estate professionals who, like Sean, who are based in the upper Midwest, climate change is actually a wind at their backs. It's real estate investors and operators in climate vulnerable places for whom understanding climate risks is a business imperative.]

The topline takeaway here is that most real estate professionals haven’t yet factored climate change into their thinking, modeling, and decision making. And if real estate pros aren’t yet seeing climate risk clearly and taking it seriously, most non-professionals in the housing market aren’t, either.

The net result of all this, and the key takeaway, is that climate change still isn’t priced into real estate markets. That means nearly all homes in climate vulnerable places are overpriced, and the popping of those housing bubbles is still to come. It means homes in climate durable places are still undervalued, and the rise in real estate values due to climate risk reassessment is going to happen in the years ahead.

This is a very big deal, and I’ll be writing more in the coming months about how to think about it and what to do about it.

People who own real estate in financially durable places will benefit financially whether or not they anticipated what was coming. Luck plays a huge role.

That’s why those markets are so expensive, and part of why proposals for new building usually run into significant opposition.

Welcome back. So glad you are feeling better.