Does climate change threaten your home equity?

Homeowners and home-buyers need to consider climate risk in buy/sell decisions

When I started writing about climate change and destabilization I was struck by the gap between the foreseeability and stakes of the coming disruption to the housing market on the one hand, and the lack of attention it was getting on the other. That’s why I’ve written so much about the nexus of climate risk, rising home insurance premiums, and the looming threat to home values in vulnerable locations.

The rising cost of home insurance has begun to get more attention recently, spurred by insurance market turmoil in climate vulnerable states including California, Florida, and Louisiana. For instance, USA Today recently wrote, “[W]hether or not you believe climate change is a problem, your data-driven insurance company already does.” This is good, but there’s still a lack of understanding about what growing climate risks mean for home values.

Climate change is a real and growing threat to the value of climate vulnerable homes, which means everyone who owns or is buying a home needs to understand its degree of exposure to climate risk. Specifically, everyone needs to:

Understand climate change

Analyze how it is likely to impact a particular home, physically and financially

Assess to what degree those climate risk vectors can be mitigated

Factor the risks into their decision making

In 2023, failing to do this is a personal finance screw-up on the scale of neglecting to sign-up for your employer’s 401k. There’s a chance you’ll get lucky and things will be okay, but there’s also a chance your house will decline in value as insurance and other costs rise and home buyers start factoring climate risk into their offers.

This mistake has already ruined people financially, and it threatens to bite more and more families every year. Analyzing your home’s exposure to climate risk and acting accordingly is a crucial climate change era financial practice. And making the correct judgments about which home(s) to buy, which to sell and avoid, and how to ruggedize your home against a variety of risks is already one of the essential financial skillsets of the 21st century.

Here’s an example to illustrate how the value of a climate durable home (blue line) will tend to change over the coming decades compared to the value of a climate vulnerable home (orange line). And this example isn’t an outlier, other climate vulnerable homes will see their value fall further and faster than this one.

In the past, the outcomes of homeownership were lower variance. As a result, our common sense and cultural assumptions about home-buying lull us into a false sense of security with the promise that buying a home is a good investment, period. That used to be true. What’s true now is that some homes are a good investment, while others are a financial calamity waiting to happen.

Climate change basics

Let’s briefly remind ourselves of how climate change works and why it’s increasing the risk to houses, apartment buildings, other dwellings, and all physical structures. Climate change, as we know, is the heating up of the earth due to higher levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere capturing and holding more of the sun’s energy. As temperatures increase, moisture evaporates more rapidly and warmer air holds more water vapor. This leads to more drought in some areas and more intense precipitation in others, as clouds eventually release the moisture as rain. Increased temperatures also mean higher sea levels, partly from warmer oceans and partly melting glaciers.

Warmer water and higher sea levels mean more powerful hurricanes with bigger, more destructive storm surges. Heavier rain means more flooding. Drier conditions means more wildfires. And these and other climate change-fueled extreme weather events will continue to worsen as long as we keep adding GHG to the atmosphere.1

In The climate crisis means destabilization, not doom, I gave some specific examples of climate change-fueled extreme weather events and how they affect us. Here’s one:

For more than 37 years, from July 1967 through August 2004, the most rain that ever fell in a single hour in New York City’s Central Park was 1.58 inches. Then in September 2004, 1.76 inches fell in an hour. This record stood until August 21, 2021, when 1.94 inches of rain came down in sixty minutes. The two previous New York City records for rainfall in an hour had lasted for 37 and 17 years, respectively, but this one would last just 11 days. On September 1, 2021, over the course of one hour, Hurricane Ida dropped 3.15 inches of rain on the city. A record broken twice by 0.18 inches was obliterated by 1.21 inches. The deluge caused widespread flooding, in which eighteen New Yorkers died.

Here’s another:

Before 2021, the *least* amount of rain that had ever fallen in the Denver-Boulder area between July 1st and December 29th was 2.09 inches in 1962. The next lowest readings were 2.15 and 2.29 inches in 1939 and 2003. In 2021, over the same 6-month window, just 1.08 inches of rain fell. If that weren’t enough, in an average year Boulder gets about 30 inches of snow between September and December; in 2021, only 1.46 inches fell. In the resulting crispy-dry conditions, a fire ignited in the Boulder suburbs on December 30, 2021. Despite the largely manmade environment, the fire spread rapidly in high winds. The unprecedented winter blaze burned 6,200 acres and destroyed 991 homes. One person died.

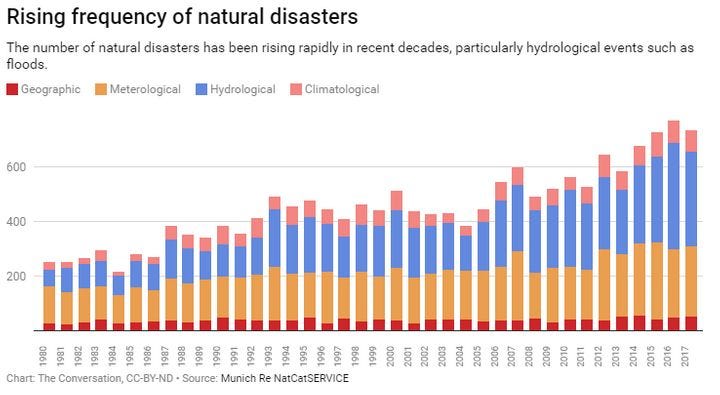

These are just two examples of too many to track. China’s heatwave and Pakistan’s flooding in summer 2022, and Australia’s wildfires in 2020 were only the highest profile of the many unprecedented and destructive natural disasters that have ravaged the globe in recent years. The number of lives ended and torn apart, and the number of properties damaged, is difficult to track. But it’s a lot. And more every year.

How climate change affects property insurance

Climate change will drive up a number of the core “operating costs” of owning a home, including repairs and maintenance, property taxes, and utilities. I’ll go into more detail about these in future posts. But the cost of homeownership subject to the largest climate-driven increases is home insurance premiums.

Climate change affects the cost of home insurance (and all insurance of physical property) for a straightforward reason: more and bigger natural disasters —> more damage to property —> more and more expensive insurance claims.

When we talk about insurance we’re unavoidably talking about the private businesses that provide it, and for any business to be sustainable, revenue has to exceed costs.2 If it doesn’t, the business will eventually go under, as many insurance companies in climate vulnerable states already have.

In the insurance business, costs are operational expenses (compensation, rent, computers, paper clips, etc.) plus claims payouts. Revenue is insurance premiums. Because increasingly severe natural disasters are driving up claims payouts, for the business to work premiums have to rise, too.

But because insurance companies operate in competitive markets, they can’t just raise all home insurance premiums. If they did, their customers with lower risk homes would go into the market and find a fairer, better deal from another insurer. Instead, insurance companies have to offer each customer a competitive rate that reflects the level of risk of their individual property.

The result is inevitable: the cost of insurance for climate vulnerable homes is skyrocketing. It will keep rising for years to come. Meanwhile, the cost of insurance for climate durable homes is relatively steady. In both cases, the cost reflects the risk.

How rising insurance costs affect home values

It’s obviously bad for a homeowner when the cost of their insurance rises. Having to pay more for the same thing is unwelcome, and it’s especially bad when it’s something you can’t do without.3 But I’m not sure people fully realize what will happen if their home insurance premiums rise.

In Climate change and housing bubbles, I analyzed two homes that each cost $750,000, one climate vulnerable and one climate durable. Both start with home insurance premiums of $300/month. The climate vulnerable home then sees its premiums increase to $1,000/month. This increase causes the value of the home to fall by $195,000, more than 25 percent.

You can read the full analysis in the original post, or below in footnote 4.4 You can also review the analysis itself in the original spreadsheet model I created. Feel free to copy it (File—>Make a copy), tweak the inputs, and customize it for yourself.

One can nitpick the specifics of this example - the increase in insurance premiums is large (it would happen over more than just one year), the mortgage rates are low, the house price is high or low - but the principle is unimpeachable: having your home insurance premiums increase isn’t just a generalized bummer, it actually decreases the value of your home.

This is the picture we should have in mind in considering what home we want to own:

In the years ahead, those who understand and factor climate risk into buy/sell decisions about their home will thrive financially. Those who don’t will be tempting fate and inviting financial disaster.

The logical next question is how, exactly, to identify climate durable homes and distinguish them from climate vulnerable homes. I’ll be writing more about this soon.

Obviously, this is why producing more and more renewable, non-carbon electricity (solar, wind, geothermal, etc.) and simultaneously electrifying everything is so important.

Our recently concluded decade-plus of ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) notwithstanding.

There are people who don’t have insurance, and unless they’re so rich they can comfortably self-insure it’s an insanely risky and inadvisable thing to do. If you own a home but can’t afford home insurance, it’s a much better financial decision to sell your home and rent instead. That way all of the equity, the wealth, you’ve built up in the home isn’t at risk of being completely wiped out in a big storm or other unforeseen disaster.

Analysis from Climate change and housing bubbles:

[L]et’s consider two hypothetical homes, Home A and Home B, both on the market for $750,000. Home A is in a climate vulnerable place where home insurance premiums haven’t yet been repriced to reflect the risk. Home B is in a place that’s less vulnerable to climate change and where current insurance premiums are still a fairly accurate reflection of the potential for damage to homes.

Let’s say Person A buys Home A and Person B buys Home B, both for the asking price of $750,000. They both put down 20% ($150,000) and both borrow the remaining $600,000 at a fixed interest rate of 3.5% over 30 years. Both pay $1,000 per month in property taxes and $300 per month for homeowners insurance, so both have the same total monthly payment amount:

Mortgage payment: $2,694 ($600,000, 3.5% fixed, 30 years)

Property taxes: $1,000

Homeowners insurance: $300

Total: $3,994 per month

This number, $3,994 per month, represents what Homes A and B are worth; it’s the $750,000 sale price translated into a monthly amount. The market value for both Home A and Home B is $3,994 per month, and given tax and insurance payments of $1,300 per month, that leaves $2,694 for the mortgage payment.

Now let’s say the provider of insurance for Home A does a new risk assessment and determines the home insurance premiums don’t reflect the actual risk to the home. To bring the premiums in line with the risk, the insurance company raises Person A’s rates from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Increased home insurance rates are usually discussed in terms of the additional cost burden on the homeowner, which is obviously a critical perspective. But what I want to know is: how much can Person A now sell Home A for if they decide to move?

We established Home A is worth $3,994 per month. When Person A bought Home A, only $1,300 of the total amount was taxes and insurance, but now taxes and insurance have increased to $2,000. That means the mortgage can now only be $1,994, rather than $2,694, in order to stay at the established fair market value of $3,994 per month. If we assume the next buyer of Home A will also put down 20% and take a 30-year mortgage for the rest at 3.5%, how large a mortgage can the next buyer take out and still end up with an all-in cost of $3,994 per month?

The answer, via this spreadsheet model, is $444,054. Borrowing $444,054 at a rate of 3.5% fixed over 30 years comes to a monthly payment of $1,994. Adding the 20% down payment to the mortgage amount gives us the new fair market value sale price of Home A: $555,067.

Thus, when Home A’s home insurance premium increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month, the value of Home A fell by $195,000, from $750,000 to $555,067. If the insurance repricing occurred in the first few years of ownership, Person A would see all of their equity wiped out and be left underwater, owing more on the home than it was worth – this despite their large $150,000 down payment.