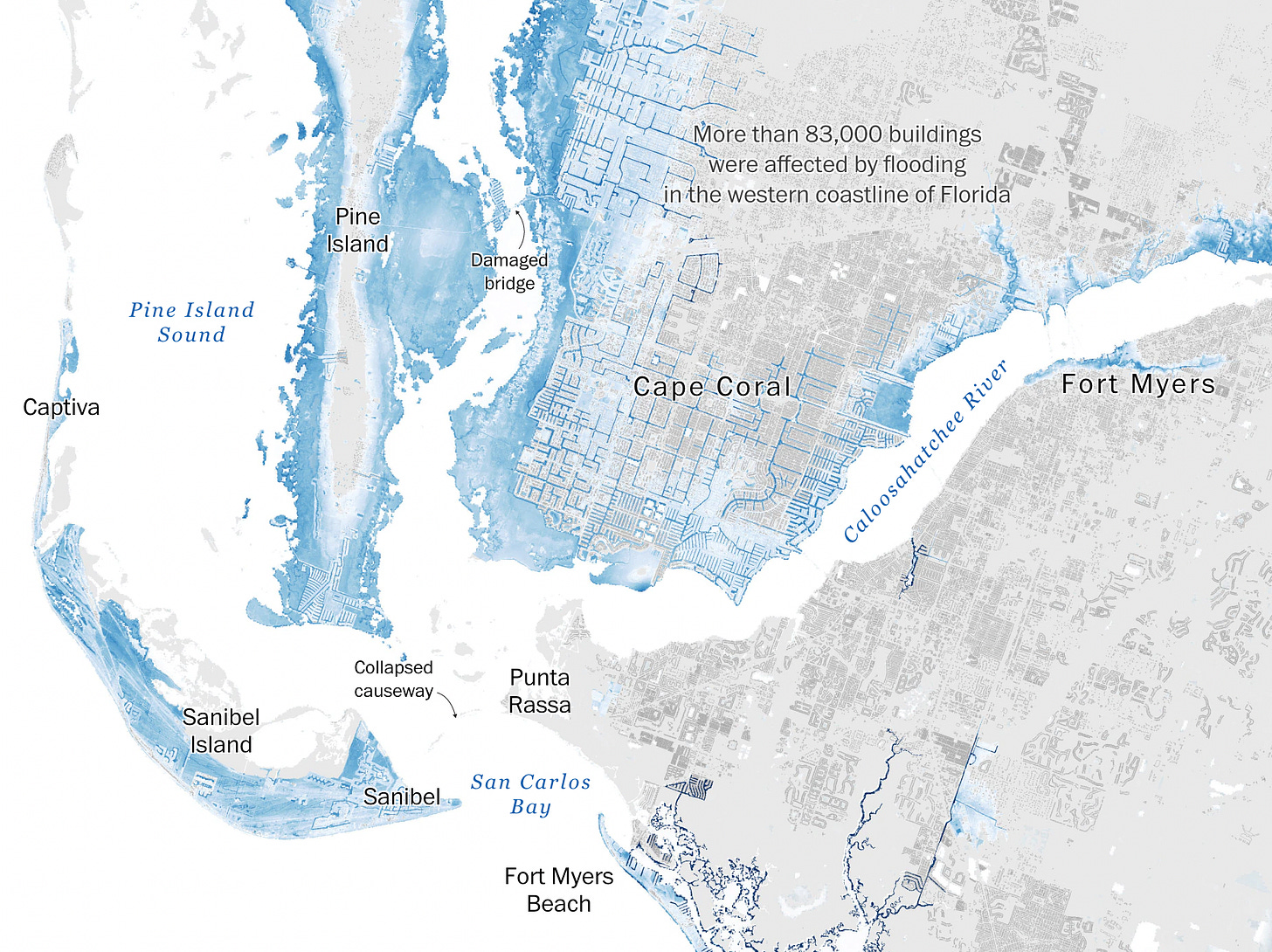

September 28th, 2022, the day Hurricane Ian devastated southwest Florida, may go down in history as the beginning of the end of Florida as an attractive, affordable place to live. Ian’s wicked 150-mph winds and towering 12-foot storm surge annihilated nearly everything in its path in Sanibel, Fort Myers Beach, Cape Coral, and other communities in the region. It’s difficult to overstate the extent of the destruction.

Ian caused an estimated $70 billion in privately insured damages, making it the second most costly storm in U.S. history, behind only Hurricane Katrina. Making it far worse, most people weren’t adequately insured. In big hurricanes, water causes far more damage than wind, and in the counties ordered to evacuate for Ian only about 19 percent of residents had flood insurance. Even in FEMA-designated flood zones only 47 percent of homes had federal flood coverage, but among those not in official flood areas, many of which nonetheless experienced severe flooding, only 9 percent of homes were covered.

The first takeaway here is that many thousands of Americans in Ian’s path not only had their lives disrupted, but were financially ruined as well. Most will not get to live the lives they were anticipating just a month ago, and many will exist in financial precarity for months and years to come. It’s a profound human tragedy.

—

As is often the case in the climate change era, Ian’s ripple effects may ultimately do the most damage, in both human and material terms. We can’t know for sure what will happen in the future, but if a few things go the wrong way, life in Florida may start to unravel. If the unraveling does begin, there is a real danger it could take on a logic and momentum of its own, which would make it difficult to reverse. (Shout-out to Christopher Flavelle at the New York Times, who explained these dynamics lucidly in a recent episode of The Daily.)

Here’s a sequential account of how and why Florida might begin to unravel in the wake of Hurricane Ian.

First, the privately insured damages from Ian would have to be very high. This one has already happened: we know the insured damages are massive. This will likely push some insurance companies into insolvency (six Florida insurance companies had already gone bankrupt in 2022 before Hurricane Ian), and require most of the rest to fall back on reinsurance.

Next, when Florida insurers’ reinsurance contracts come up for annual renewals in the coming months, the big reinsurers either drop them or significantly increase their rates. This will happen if reinsurance companies reassess their view of Florida’s property market in light of Ian and climate change, determine it is riskier than they had accounted for, and raise rates to reflect the high and growing risk. This will almost certainly happen, the question is to what degree.

[Important note on reinsurance: Florida-domiciled insurance companies have a slightly different operating model. Rather than holding large cash reserves to cover future claims, as most insurers do, many Sunshine State insurers instead cover their exposure using reinsurance. The result is Florida’s housing market is backstopped by, and therefore reliant on, large reinsurance firms.1]

If prospective home buyers can’t access home insurance, they generally can’t get a mortgage. If buyers can’t get mortgages, the market for buying and selling homes would nearly evaporate, causing home values to crash.

If buyers can only access really expensive property insurance, the value of homes also plummets (as I detailed in Climate change and housing bubbles), though not quite as catastrophically. In this scenario, even renting becomes expensive because landlords have to cover their now-elevated insurance costs. (Even if a future landlord bought a building at a large discount, rents wouldn’t fall by much because the discount on the building was available specifically because of hugely expensive insurance.)

Florida’s economy is built on housing more than in most states. If its housing market craters, the entire state economy will pulled into a deep recession. Some people will leave, which will further compromise home values. The unraveling dynamics are not hard to imagine.

Is such an unravelling likely to start soon? It’s complicated, but no. The state has some key levers it can pull that will likely push it out some years. First, Florida has a state-sponsored insurer of last resort, Citizens, that may be able to prop up its insurance market, at least for a while. But this strategy would have limits, including that Citizens needs reinsurance even more than private sector insurance companies do because it insures the riskiest properties in the state.2

If it loses access to reinsurance, as it may given its scary risk profile, Citizens has another back-up plan. It has the statutory right to raise cash to pay claims through surcharges on various Florida insurance policies (not just property, but car, boat, and other kinds of insurance, as well). Most Floridians pay for some kind of insurance, so this fallback option would be, in effect, the imposition of a statewide tax. For a state that prides itself on, and attracts new residents with, the promise of zero income tax, the political viability of such an approach is questionable. But if the alternative is the state housing market crashing, it’s certainly the better option.

It’s also possible the federal government might bail Florida out after a calamitous future storm, perhaps by injecting cash into Citizens to pay claims.3 But the policy justification for doing so only in Florida would be iffy at best. If the federal government pays for climate disasters in Florida, why not climate disasters in Utah? Kentucky? California? There’s no valid neutral principle that justifies propping up Florida but not other states, and not even the U.S. government has enough money to cover climate disasters across the whole country. Saying something is unprincipled, however, isn’t the same as saying it’s unlikely, and a future federal bailout for Florida is probably a coin flip. But even if it happens once or twice, calamitous storms will keep happening, while bailouts likely will not.

So what will happen? Someday, South Florida will unravel, the dynamics of which I’ve described here and here. When it eventually starts, the process could unfold especially rapidly since South Florida has both lots of transplants and lots of real estate owned by foreigners who are mostly interested in a safe place to park their cash.

One final point, which is key to understanding the big picture. The reason the price of home insurance in Florida is going to rise, if it remains available at all, is that the risk of living there is high. Residents of Miami, Sanibel, Cape Coral, Tampa, and other climate vulnerable areas will pay a lot more for home insurance than people in Milwaukee, Denver, or Ithaca for the same reason a cargo ship crossing the Pacific Ocean during typhoon season costs more to insure than the same ship crossing Lake Erie in the spring: one situation has a much higher likelihood of damage and loss than the other. No reinsurance scheme, state market intervention, or system of insurance surcharges can alter that core reality. And the risks in Florida – and the gap between it and more climate durable places – will only increase in the years ahead.

It’s beyond the scope of this post, but the reason Florida has these smaller, state-focused insurers that rely heavily on reinsurance is the big national insurance companies stopped offering property insurance in much of the state following Hurricane Andrew’s widespread destruction in 1992.

Citizens has a coverage cap of $1 million in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties and $700,000 in the rest of the state, although the caps can be changed legislatively.

This could be an act of Congress or the executive branch repurposing funds intended for something else.